Byrle G. Walker, a 34-year-old teacher from Idaho Falls, Idaho, was working part-time for the U.S. Forest Service, when he set out to inspect trees and do insect control work in the Targhee National Forest on June 7, 1967, in Ashton, Idaho.

After getting permission under a schoolboy work permit, Walker brought his nephew, Kristan C. Sparks, 13, also from Idaho Falls, and Sparks’ friend, 14-year-old James Allen Black from Nampa, Idaho. That day they were tasked with picking up empty cans that had been left behind when the trees were treated with insecticides the previous fall.

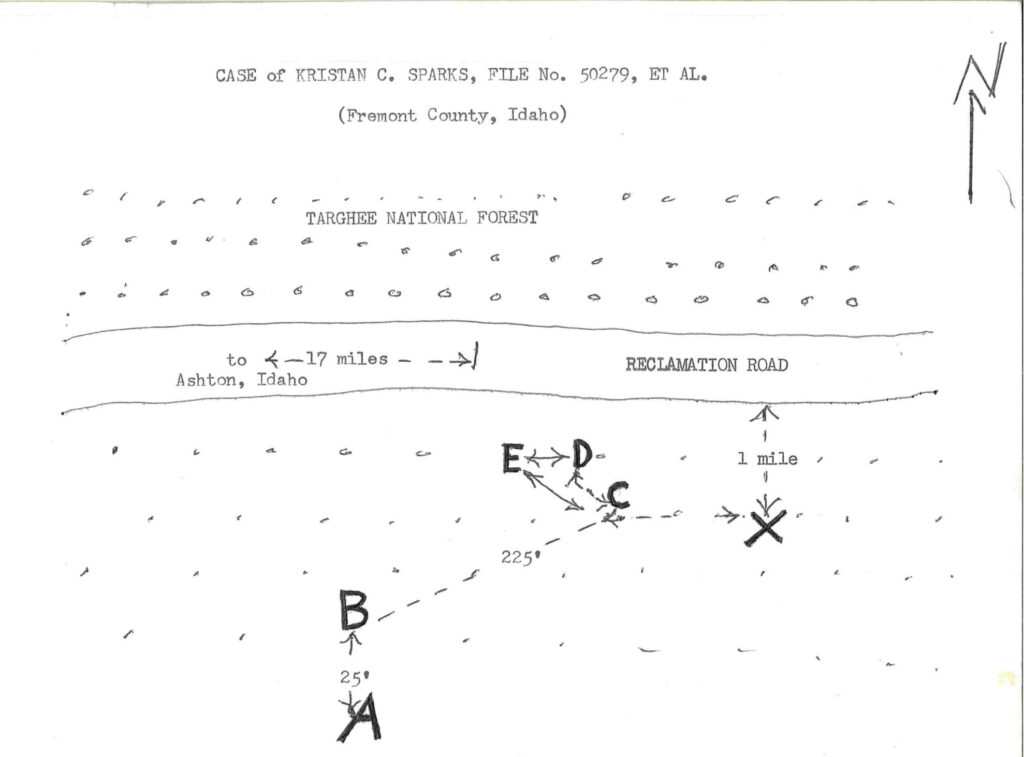

In an account written by Walker to the Boy Scouts of America, the three of them drove down a road about 2.5 miles above their camp and encountered deep mud holes. They stopped to search for cans after moving through an especially deep area of mud.

“Where we stopped wasn’t where I wanted to go but I thought we may as well see what we could find there,” Walker wrote.

The three of them moved east inspecting different rows of trees for the discarded containers.

“The boys and I were in separate lanes of trees which had been roped off for treatment,” Walker told reporters. “We were going to walk down those lines to look for the cans,” he said.

But as Walker pushed on a bit farther, he said later that he wondered if a bear could have been in the area. Despite failing to see any tracks, Walker found torn apart logs, which he believed a bear could have done while searching for food. He did not initially tell the boys what he had seen.

Walker thought he heard grunting and turned around to spot a male grizzly bear north of him, which Hero Fund Investigator Irwin M. Urling recorded as at least 350 pounds.

Kristan told reporters that he and James originally thought the sound of the bear was an elk “bugling.”

Walker moved away from the boys, after shouting at them to run, he began to holler at the bear in an effort to frighten it off.

“I looked back and saw this bear angling off my trail,” Walker told the reporter. “Evidently he had caught my scent and started for me at a dead run. First, I tried to climb a tree, but there wasn’t enough time, so I started running.”

Walker ran east, but the bear intercepted him. The animal knocked Walker to the ground and began to bite him; he cried out in pain.

The Attack Begins

“The bear knocked me down, and started chewing on my neck, scalp, both shoulders, fanny, and side,” he said.

Kristan and James continued to flee, but the sound of Walker’s screams and the loud growling of the bear stopped them.

Kristan and James stopped 75 from the scene; they could see the bear mauling Walker. The boys shouted at the bear to draw its attention from its prey. Despite their efforts, the bear paid no mind to them and continued to maul Walker.

In his own written account for the Boy Scouts of America, Kristan eluded to the conclusion that the bear was being territorial or protective. “The bear acted like he was doing it because he had cubs or something,” Kristan added. “We weren’t sure though because we didn’t see any cubs.”

They tried to throw twigs at the animal, but the small twigs would not carry that far. The boys continued to shout and then used sticks to beat on the trunks of surrounding trees.

The bear turned once toward the boys and went back to Walker. As the teens persisted in making noise, the animal finally took notice. It stopped its attack on Walker.

“I have never had such a relief in my life as to have him leave me,” Walker said.

The large animal lifted its front paws off the ground to stand on its hind legs and emitted a loud bellow.

Kristan told James to flee and the boys separated. James turned north, and the bear ran in a similar direction after him.

The Chase

He said later that he could feel the aggressive animal on his heels as he ran through the dense brush.

The bear caught up to James, overtook him, and knocked him to the ground, but it quickly moved on from him, and continued its pursuit of Kristan. The bear reached Kristan after he had run about 150 feet. The bear seized his left wrist with its mouth and threw him to the ground. It bit deep into his left forearm and wrist, but Kristan played dead.

The bear ceased its attack on Kristan, but its aggressive assault was not done. It returned to James.

James wrote in his own account that he grabbed a stick and attempted to hit the bear in the face, with no success.

Meanwhile, Kristan had fled, running toward the road and then to camp as fast as he could.

“I was going to stop at the truck that we had driven up in, but the truck door was open and I was afraid there would be another bear and so I kept running past it,” he said.

About a mile into the journey, he stopped to remove his footwear. “When I reached the road, I took off my heavy boots and socks in order to run faster, and I made better time after that,” Sparks told the Twin Falls Times News. “I thought the others were dead.”

In a letter to the Boy Scouts of America, Mary Walker, Walker’s wife wrote about Kristan’s actions once he got to camp.

“Kristan had made no move to even enter the safety of the trailer, and he hadn’t even mentioned or apparently thought to see to his own needs,” she wrote.

“Kristan fully intended to take us back to his place of horror, not once thinking of finding a secure place … In fact, his whole concern seemed to be to get effective help back to the other men as soon as possible.”

The Bear’s Last Victim

Back in the forest, James was not able to hurt the large bear, so he turned to face the ground, wrapping his arms around his head to protect it. The bear bit into his left arm. The force of the bite fractured his arm. The bear then bit James on his right arm and thigh.

Then it all … just stopped. The bear stopped its attack and trotted off to the south, never to be seen again.

James said he stood and followed the bear to make sure it was leaving the scene. Then he went to the road and started back toward camp to get help.

“I thought these other guys were dead,” he said. Walker, too, eventually “got to [his] senses” and stood up. He hollered for the kids, but no one responded. He went out to the road where he waited for help.

“I thought I was bleeding to death,” he said.

Eventually he made his way to the truck and headed back toward camp, and he was reunited with Kristan and James. They were all taken to the hospital.

Walker required the most extensive care. He received 300 sutures to wounds on his head, neck, arms, and shoulders. He was hospitalized for 10 days before he recovered.

James sustained a compound fracture to his left arm and required 17 sutures on both arms, as well as his thigh. He did not fully recover for about eight weeks due to the fracture.

Kristan needed 10 sutures all on his wrist and forearm. He recovered after seven days in the hospital.

According a June 12, 1967 article from the Deseret News, hunters with dogs attempted to track the marauding bear, but no trace of the animal was found after they pursued it across the Idaho-Wyoming border.

The Aftermath

Following the incident, both Kristan and James were nominated by Walker for the Boy Scouts of America Honor Medal.

“If he had taken any more bites out of my head, there would have been some real damage done. I hate to think what would have happened if I had been alone,” Walker wrote. “Jim Black and Kristan Sparks were faced with a decision. They made their decision and in the process it drew the bear from me and it cost them some hurt and a real experience in the process.”

Through the Boy Scouts award, the Hero Fund became aware of their act of bravery in drawing the bear away from injured Walker.

Kristan and James were awarded bronze medals from the Hero Fund. Each would later receive grants to assist in their education after they graduated from high school. Their story appeared in the May 1971 Golden Comics Digest, published by Gold Key. Kristan went on to become an optometrist in Idaho Falls, and James currently serves as a field service engineer for a healthcare company in Meridian, Idaho.

– By Griffin Erdely, Communications Intern