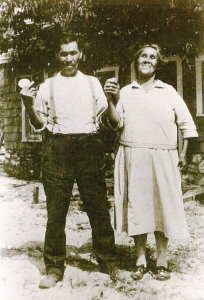

Don Stoll of Good Hart, Mich., is the great-grandson of Joseph Okenotego, one of the first Native Americans to be awarded the Carnegie Medal, and 108 years after his great-grandfather’s heroic act, the Hero Fund gave him a grave marker cast in the likeness of the medal to further commemorate his heroism. Stoll, who according to locals “lives simply and follows the old way,” remains on his great-grandfather’s property, on the east shore of Lake Michigan near the tip of the state’s Lower Peninsula. Okenotego, who died at age 89 in 1942, is buried in nearby St. Ignatius Cemetery. Stoll is a member of the Grand Traverse Band, consisting of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians.

Initially forgotten after its occurrence on Nov. 8, 1908, the heroic rescue act was called to the Hero Fund’s attention in 1910 by Father Agatho Anklin of Harbor Springs, Mich., a Catholic missionary among the Ottawa (Odawa) Indians. While researching the incident, he was assisted by Mother Mary Drexel, who was canonized a saint in 2000. Hero Fund investigators looked into the case in 1911 and 1914, and awards were made in 1914 to both Okenotego and his co-rescuer, Joseph Kijigobinessi, also a Native American. Grants of $500—the equivalent of $12,000 today—were given to the men.

Okenotego and Kijigobinessi were named heroes for rescuing three men from their storm-tossed boat on Lake Michigan at Good Hart. Although more than 100 years have passed, the story of their heroism is kept alive by family members, local historians, and researchers. Accounts of it appear in books The Indians of Hungry Hollow and The Place Where the Crooked Tree Stood; in Traverse, Northern Michigan’s Magazine; and of course in the files of the Hero Fund, which has retained a copy of the investigator’s 1914 case report.

A forceful storm that struck the northern end of Lake Michigan in early November 1908 left William Prout, Alfred Shampine, and Amab Lavake, all fisherman, stranded in their 28-foot, gasoline-powered boat on the sixth. The men were homeward bound when their boat’s engine failed in strong winds and waves from six to eight feet high. They put down an anchor but it did not hold, and at the mercy of the seas they drifted, without food, until the following afternoon. When the anchor did take hold, at a point about a half-mile from shore, the men decided to wait out the storm rather than risk going ashore amid the high breakers, even though all were “cold and faint” in the 40-degree air. They hoisted a distress flag.

On shore, Okenotego, 53, and Kijigobinessi, 37, noticed the men’s plight, called for a rescue tug, and built a fire on the beach as a signal. The storm continued unabated that night, and by the next morning, hope was waning that a tug would appear. Okenotego and Kijigobinessi volunteered to take Kijigobinessi’s boat into the lake and attempt a rescue. They obtained the 16-foot, flat-bottomed, wooden vessel from a point 1.5 miles away and launched it, Kijigobinessi handling the oars and Okenotego tending the rudder.

As the men proceeded, the boat was tossed so that it stood nearly on end, and they bailed out shipped water with a 10-quart can. Those on shore lost sight of them in the high seas, and a lone man sang a bravery song on the bluff overlooking the lake as they challenged the storm. Once Okenotego and Kijigobinessi reached the stranded vessel, Prout snagged the rescuers’ boat with a pike pole, and he and his companions boarded it. The rescue boat contained considerable water and with the added weight of the men sat low. Okenotego and Kijigobinessi took the craft straight toward the beach. The first set of breakers nearly swamped it, and the second set threw it 60 feet forward, leaving it stranded about 20 feet from shore. Those on the beach ran out and pulled it in, two hours after the rescue commenced, and all five men survived.

—Susan M. Rizza, Case Investigator, contributing.

Return to imPULSE index.

See PDF of this issue.