Under-lake tunnel disaster prompted intense Hero Fund investigation to determine rescuers’ actions

The rescues that occurred after the 1916 Cleveland Waterworks Tunnel Disaster required Hero Fund Investigator A.W. Crawford to parse even the minutest details to accurately determine the specific actions of the 22 men nominated for the Carnegie Medal for their role in the rescue efforts in the disaster that ultimately left 20 men dead and others hospitalized. The goal of the investigation: to determine who among the 22 nominees knowingly risked their lives to an extraordinary degree to save others whose lives were in imminent danger.

Not only were there complicated technical details to learn about the construction of an under-lake tunnel, but there were also limited eyewitnesses, as those involved in the first rescue attempts died. Additionally, mistaken assumptions about the investigation of this case continue to force the Hero Fund to defend the integrity of the 84-year-old investigation. We thought it was time to set the record straight.

Investigator Crawford was sent to Cleveland only two months after the names of 22 men crossed the Hero Fund’s desk via an Aug. 16, 1916, letter from electrical engineer H.R. Bailey who worked on the tunnel construction project. (Bailey’s involvement in the rescues, if any, remains unknown.)

Investigation of the accident begins

It was around 9:30 p.m. on July 24, 1916, in Cleveland when methane gas that vented during the construction of an underground tunnel ignited and exploded burying nine men under hundreds of feet of mud and construction debris under Lake Erie. Concrete blocks that lined the tunnel were forced through the tunnel ceiling, and the blast mangled railroad tracks and threw boards, wires, and machinery into an indistinguishable “mass on the floor of the tunnel,” according to Crawford’s report to the Hero Fund Commission. All the lights flickered out except for one at one end of the tunnel nearest an air-locked chamber. The nine workers were killed instantly, but no one above ground — including a crew of about 20 stationed at the structure directly above the tunnel — heard the explosion.

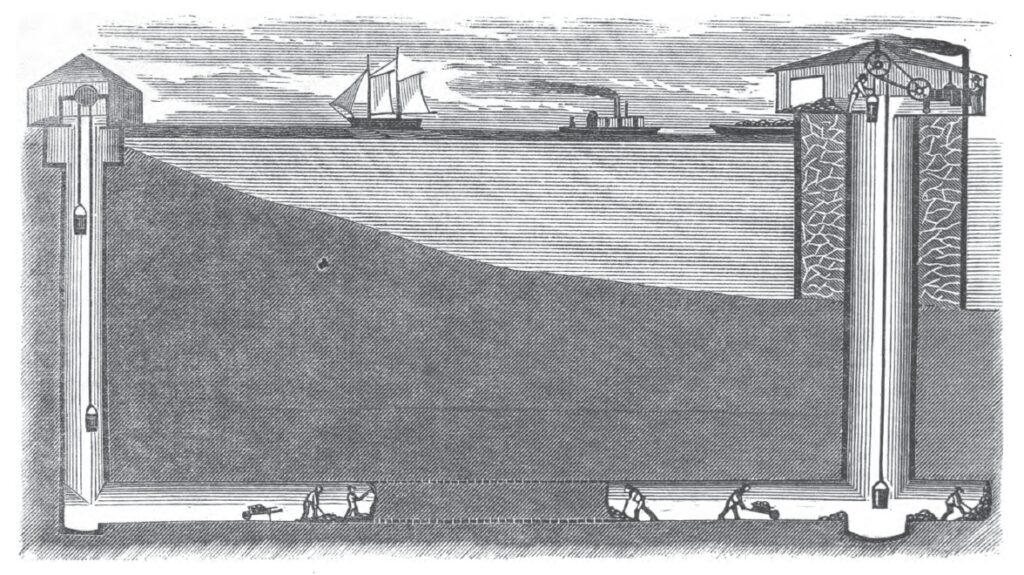

For the previous six decades, Lake Erie had provided drinking water to Cleveland citizens, but after the Civil War, industrialism and an ever-growing, urban population polluted the lake especially along its shores. According to a Cleveland Historical article by Jim Dubelko, complaints about tainted water led to the 1874 construction of the first tunnel that enabled water companies to take less polluted water from farther offshore.

The men in the 1916 accident had been working on the construction of a fourth tunnel intended to stretch four miles under the lake’s bottom from a pumping station on shore to a structure called a crib located at the lake’s surface. Typically during the construction of these tunnels, crews worked from both ends and moved towards one another until they met in the middle and the tunnel was completed: Access to each end of the tunnel was via vertical shafts at the pumping station and the crib.

The methane explosion had occurred at the crib’s end of the tunnel. At the water’s surface, the crib contained a cage on a pulley that allowed workers to be lowered 127 feet down the shaft to the 10-foot-wide tunnel. Workers had constructed about 1,433 feet of tunnel from the shaft and, at the time of the explosion, were working at the tunnel’s face, digging southward. A tenth man, lock-tender William J. Dolan, was stationed at an air-locked chamber located between the tunnel and the shaft; Dolan was responsible for adjusting valves, doors, and vents to regulate the air pressure in the construction tunnel and in the tunnel leading to the shaft. Doors from the chamber could not open unless the pressure was equal on both sides.

The explosion blew him 20 feet away and opened the shaft side door, but Dolan was not badly injured. Although dazed, he immediately attempted to regulate the pressure inside the tunnel to open the door that would lead to the workers. An engineer at the crib noticed gauges measuring erratic air pressure inside the tunnel and woke Assistant Superintendent of Tunnel Construction John R. Johnston, who was sleeping at the crib.

First rescuers go down

After an initial inspection, Johnston assembled a team of six other men, all of whom had experience with tunnel work. With two flashlights they started down the tunnel. Johnston, who was leading the group with one light, later told Investigator Crawford that he understood that the gas would rise to the ceiling of the tunnel and that he would notice any ill effects before anyone was overcome. Johnston cautioned the men to stay low and they crept 132 feet toward the debris. Johnston heard a man gasp behind him and turned to see five of the men had collapsed. The sixth had turned and ran back toward the airlock. Johnston told the investigator he felt no ill effects, but then he, too, collapsed. Dolan had left the airlock and was following behind the team slowly when he encountered the sixth man hurrying back toward the lock. The man told Dolan that the others in his party were dead. Dolan saw Johnston’s light and begged the man to help him move Johnston to safety, but the man refused.

Dolan made his way the remaining 30 feet to Johnston and yanked on his clothes, dragging him back toward the lock, repeatedly shouting for the other man to come help. When Dolan reached a point about 30 feet from the lock, the man responded and helped Dolan carry Johnston to the lock, which they sealed and continued to the shaft where others pulled all three men up. Dolan told the investigator that by the time he got to the top of the shaft he was feeling quite ill and vomiting.

Meanwhile, someone alerted Gus Van Duzen, superintendent of tunnel construction. He made his way from his Cleveland home to the scene, but while boarding a tugboat to get to the crib, he ran into 12 tunnel workers who were ending their shift in another tunnel. He asked them to help with the rescue efforts, and all 12 of them agreed. When he arrived at the scene, Van Duzen was told that three men had been taken to the hospital, but due to chaos at the scene, no one told him or the other men that most of the first rescue party lay dead in the tunnel.

Second rescuers go down

Van Duzen and nine of the workers were lowered into the tunnel. Some men were left at the airlock including experienced lock-tender Jesse L. Hatcher to operate it. The others moved forward into the tunnel, where they eventually encountered the five men left behind from the first rescue attempt. It was here that members of Van Duzen’s party began collapsing. Van Duzen shouted for the others to run back to the lock before he, too, was overcome and collapsed. A valve inside the lock was left open and gas was leaking into it, causing the three men inside to collapse and gas to leak into the shaft. The doors in the chamber were sealed shut and could not be opened unless someone inside equalized the pressure. With no one able to operate it, even if the men made it to the airlock, they would not be able to escape the spreading gas.

It was now 2:30 a.m. Word had reached James J. Keating who went to the scene with Thomas J. Clancy, Van Duzen’s step-son. At the crib they learned of the two failed rescue attempts and were urged by others to stay at the crib, but they entered the cage with James McGrath. “There was then so much gas in the shaft that [people] who leaned over it were made sick and dizzy,” wrote Crawford in his report.

Third, fourth, fifth, and sixth rescue attempts

Keating, Clancy, and McGrath had difficulty breathing while being lowered down the shaft, but once at the bottom it was easier to breathe, they said later. After looking into the lock and seeing the men collapsed inside, Clancy broke a window in its door to open it. After waiting 10 minutes to allow the gas to escape the airlock, they entered and found two of the men — Hatcher and Peter Sullivan — still alive. They put them and the other man, John J. McCormick, into a nearby mine car and pushed it to the shaft. All three rescuers were sick and dizzy.

The cage was hoisted and by the time it reached the top, Hatcher was also dead, and the rescuers were vomiting, dizzy, and fighting headaches. Officials at the crib let no one else enter the tunnel for hours even while Clancy and Keating begged to go down to finish equalizing the pressure in the airlock to allow the door to the workers to open. Eventually officials relented and allowed Clancy and McGrath to enter again to work the valves and release the pressure inside the tunnel.

With towels over their faces they descended again and went to the lock and started opening every valve. Before they could finish they began to feel weak and dizzy. “Keating’s head felt hot and light, and he was beginning to choke,” Crawford wrote. They ran back to the cage and were hoisted immediately to the crib where they were given hot milk. They vomited and were left “weak and nervous,” according to Keating’s report.

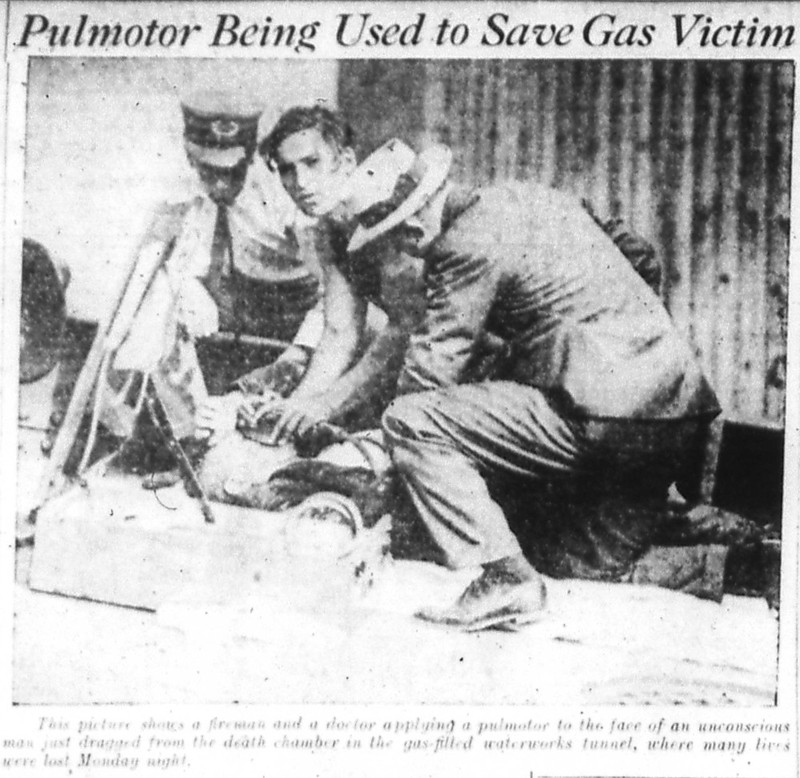

At 5:30 a.m. — eight hours after the explosion — firefighters arrived with oxygen helmets, and Keating, Clancy, and two firefighters were lowered. By the time they reached the bottom, Clancy, who was the only one not wearing an oxygen helmet, was too sick to continue and stayed in the cage. The others made their way to the lock, where Keating finished fully opening the valves in the lock. Having been in the tunnel for five minutes, they returned to the cage, where they found Clancy unresponsive. At the crib, Clancy was revived after 15 minutes with a pulmotor — a portable ventilator invented in 1907 — that had finally been brought by others to the scene.

At 7:15 a.m., banging from the tunnel could be heard in the crib, meaning someone was still alive. Keating and two firefighters descended again, Keating breaking the window in the lock’s closed door to release the pressure in the tunnel. Two men from the second rescue party — Peter P. Kehoe and Martin Nelson — immediately stumbled into the airlock and the rescuers helped them to the cage. With the tunnel now completely de-pressurized, it was not safe to take the firefighting oxygen helmets back down for fear that the attached, pressurized oxygen tanks would rupture.

Morgan arrives with safety equipment

Sometime later, inventor Garrett Morgan was summoned to the scene by a police officer who had seen the demonstration of one of Morgan’s patented inventions — a smoke hood that did not use oxygen tanks, but instead used a bag of air that the user wore around their waist. Morgan’s invention — U.S. Patent No. 1,090,936 — did not have any pressure restrictions.

With several of his smoke hoods in tow, Morgan, who was barefoot, and his brother, Frank Morgan, arrived at the scene and called for volunteers. Only Frank, Clancy, and another man, Thomas Castleberry, volunteered. The first rescue party to enter the worker’s tunnel since Van Duzen’s, they all donned Morgan’s smoke hoods and followed the same path as the others and heard Van Duzen moaning. He was facedown in the mud, barely alive. Retrieving Van Duzen and another man from his rescue party who was dead, Clarence Welch, Clancy took them to the elevator and rode it to the crib, while Morgan and the rest of his party continued searching. They found one more man alive and retrieved three others who had died in the tunnel. Ultimately it took more than a month for workers to retrieve the bodies of the workers who died in the explosion. One more man, Luigi Bucciarelli, a digger who was helping recover the bodies, fell from the crib and drowned in Lake Erie; he was the 21st person who died in the accident.

Carnegie Medal recipients

Of the 22 people nominated for the award, in 1917 only four were awarded the Carnegie Medal — Dolan, Clancy, McGrath, and Keating. None of Johnston’s, Van Duzen’s nor Morgan’s rescue parties were awarded. At the time of the investigation, all nominated cases that were turned down were simply marked with “not within the scope of the Fund,” with no further details as to why. All we can do now is draw our own conclusions as to what was behind the Commission’s decision based on policy, pattern, and precedent in how the Commission has historically applied the awarding requirements.

Garrett and Frank Morgan were the only two Black men of the 22 nominated, and many recent publications — large and small — have claimed that Garrett Morgan was denied the Carnegie Medal because of his race. However, there is simply no evidence to support the claim. Black heroes were awarded before this accident — John B. Hill, a Black man awarded in 1907 — was believed to be the first — and many since.

A well-founded conclusion, then, is that the Commission did not deviate in any way in this case from what has always been its guiding principal, received from its founder: “The Hero Fund is to become the recognized agency, watching, applauding, and supporting where support is needed, heroic action wherever displayed and by whomever displayed — White or Black, Male or Female — or at least this is my hope,” Carnegie wrote in an undated letter.

In the case of Morgan, F.M. Wilmot, the Hero Fund manager at the time, wrote a Jan. 24, 1917, letter explaining why he was not awarded.

“While the act by Mr. Morgan is commendable, from the facts at hand it does not appear that it was attended by any extraordinary risk to his own life, and for this reason his case, I regret to say, has not come within the scope of the fund.”

The Hero Fund’s requirements for the Carnegie Medal have been largely unchanged since the Fund’s 1904 inception: A person must voluntarily risk their life to an extraordinary degree to save or attempt to save the lives of others.

A fair conclusion about most of those turned down for the Medal in the Waterworks disaster were turned down because they did not “voluntarily” risk their lives.

Johnston told investigators that he thought they would feel any ill effects from the gas before it incapacitated he and his men. This was not true, but without a real understanding of the risk, they did not voluntarily risk their lives.

Dolan received the award because he continued onward to save Johnston after someone had told him they had dropped dead in the tunnel. He knew the risks and kept going, which is why he was awarded the Medal.

The same could be said for the second rescue party, who had no idea that the first rescuers lay dead in the tunnel. They entered the tunnel just as ignorant to the risk as the first party.

But the third rescue party — Keating, Clancy, and McGrath all received Medals. This was because by then the gas in the tunnel had spread to the shaft and those “who leaned over it [from the crib] were made sick and dizzy.” Those men knew exactly how dangerous it was, that several people had died already, and they volunteered to be lowered down anyway.

The subsequent rescue attempts all included safety equipment, and it’s likely that the Hero Fund Commission’s rejection of Morgan for the Carnegie Medal was because Morgan’s own invention lessened the risk for those in his party from the “extraordinary degree” that the previous rescuers encountered.

“The selflessness and bravery of Mr. Morgan are not disputed,” said Eric Zahren, Hero Fund president, in a recent letter. “But the smoke hood device appears to have provided enough protection that Mr. Morgan was not at the same extraordinary risk of suffocating” as the rescuers before him.

“That in itself serves as a testament to the ingenuity of the invention and its inventor,” added Zahren.

This is not unusual — historically, less than 10 percent of cases are awarded from the more than 94,000 nominations that have been made throughout the lifetime of the Fund. Cases are turned down for a litany of reasons including, bluntly, not enough risk taken on by the rescuer. That doesn’t mean the rescuer didn’t display outstanding courage required to save a person’s life — that’s never a question that the Hero Fund asks; it just means the evidence shows they didn’t risk their life to an extraordinary degree while doing so.

Morgan’s efforts, and bravery that day — he saved more people than any of the rescuers that entered the tunnel earlier — are important and should be honored, as well as the sacrifices the first rescuers made in their attempts.

In 1991, Cleveland officials renamed a water treatment plant after Morgan. Additionally, Morgan was given a medal from the International Association of Fire Engineers for the invention. There are also three elementary schools — in Cleveland, Chicago, and Kentucky — bearing his name, as well as a street and Metro stop in Maryland.

In 2016, Cleveland held an event that commemorated the 100th anniversary of the disaster. Grandchildren of Morgan, Van Duzen, and other rescuers spoke at the event:

“Men died to bring us clean water, and we take that for granted,” said Barbara Lind, Van Duzen’s granddaughter, at the event.

— Jewels Phraner, Editor