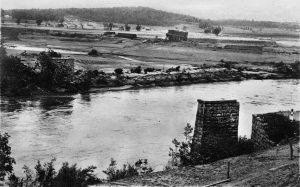

In mid-July 1916, the remnants of two hurricanes collided

over western North Carolina, inundating the mountain region and the western Piedmont with historic rainfall. The result was catastrophic. Landslides wiped out whole families. Currents ripped babies from their parents’ arms. Rivers washed away thousands of jobs. When the water finally receded, at least 50 lay dead, damages totaled in the millions of dollars, and a thick black sludge remained where crops once stood. One hundred years later, the storm remains one of the worst ever experienced in the Tar Heel State.

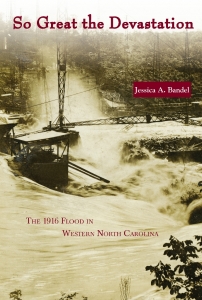

Jessica A. Bandel, a research historian with the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, summarizes the catastrophe with those words in So Great the Devastation, a recently published booklet that complements a centennial exhibit describing the flood and its effects. The exhibit is traveling throughout the western part of the state this year and will include a symposium on the flood in Asheville on July 16, 2016. An unprecedented 22 inches of rain fell in parts of the state on that date a century ago.

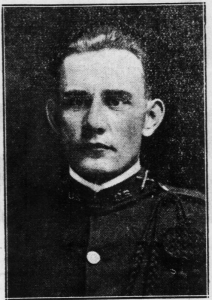

The storm revealed a “capacity for resilience,” writes Michael Hill of the state’s Historical Research Office in the booklet’s foreword. “Perhaps most noteworthy were the efforts of neighbor to assist neighbor.” One such effort led to the awarding of a Carnegie Medal, to William P. Clark. In Bandel’s words:

The storm revealed a “capacity for resilience,” writes Michael Hill of the state’s Historical Research Office in the booklet’s foreword. “Perhaps most noteworthy were the efforts of neighbor to assist neighbor.” One such effort led to the awarding of a Carnegie Medal, to William P. Clark. In Bandel’s words:

“In Morganton, Joseph L. Duckworth’s store sat 200 yards from the bank of the Catawba River. By Saturday night, however, the Catawba had begun to creep into the building. Joseph and two of his sons worked feverishly to salvage what they could from the store. When his father and brother left for the safety of higher ground, Alphonso (Duckworth) remained behind to gather money and important records. Before he could make his escape, however, a sudden surge of water marooned him. Moving to the second floor, he fabricated a makeshift boat out of lumber, passed it through a window to the water’s surface, and carefully tied it off. By morning, however, he found the boat had been swept away. The water continued to rise and poured into the second floor. Climbing to the roof, Alphonso waved frantically to the crowd gathering 800 feet away on the swollen river’s edge. The onlookers quickly raised a pledge of $1,200 for anyone who would attempt the rescue.

“Only one man stepped forward, 25-year-old William P. Clark. The six-foot-tall, 190-pound Clark put in a half-mile upriver in a 15-foot boat around 10 a.m. The 20 m.p.h. current carried him swiftly to the store, where Duckworth climbed aboard and asked to be taken around to the porch roof so that he could climb into the second floor. Clark obliged. With the records and money in hand, Alphonso returned to the boat, and the two men made their way for shore. When the townsfolk attempted to award Clark the $1,200 purse, he flatly and unflinchingly refused it, saying he would risk his life for his neighbor but not for a sum of money.

“Clark’s selfless courage would not go unrewarded. C. E. Gregory, a pastor at a Presbyterian church in Morganton, reported Clark’s heroism to the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission. Established in 1904 by American industrialist Andrew Carnegie, the fund seeks to recognize those who ‘risk their lives to an extraordinary degree saving or attempting to save the lives of others.’ Following a thorough investigation of the rescue, the Carnegie Hero Fund awarded Clark $1,000 and a bronze medal. This recognition Clark humbly accepted.”

Photograph submitted by the estate of Jean Conyers Ervin and provided by Picture Burke, a digital photograph preservation project of the Burke County (N.C.) Public Library. Thanks to Laurie Johnston of the library.

Return to imPULSE index.

See PDF of this issue.