By Brandon Abbs, Ph.D.

Pennington, N.J.

The awarding of a Carnegie Medal to Robert C. Marshall in 1954 is part of a genealogical curiosity rooted in the origins of the Hero Fund itself, reminding us that the people who have been honored by the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission are part of a culture defined by their shared choice to spontaneously risk their own lives to save others, and the Commission itself fosters this culture by recognizing them and their shared connections.

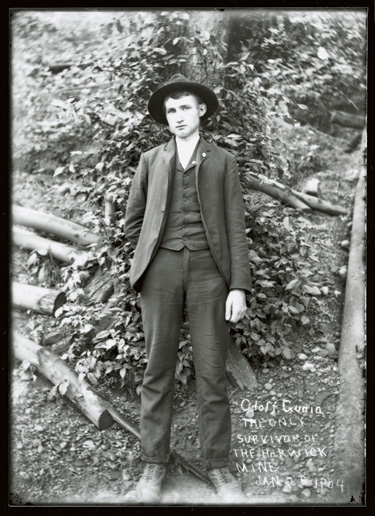

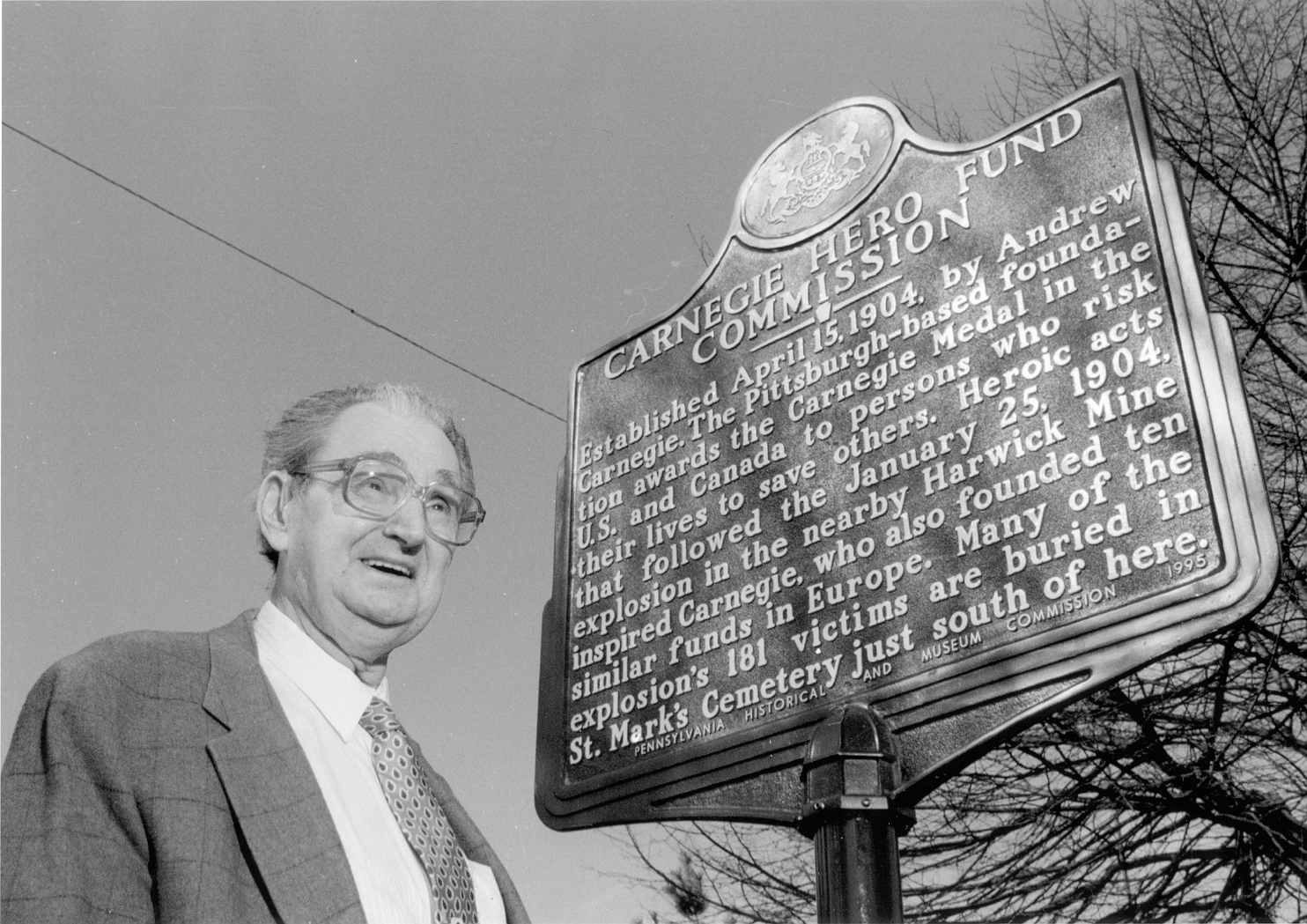

Marshall was the nephew of Adolph Gunia, whose rescue at the age of 16 famously inspired Andrew Carnegie to establish the Commission. The rescue occurred on the morning of Jan. 25, 1904, after a blown-out shot ignited coal dust and methane inside a mine in Harwick, Pa., just northeast of Pittsburgh. Gunia was one of about 180 men and boys at work in the mine at the time of the explosion and would be the disaster’s only survivor. His father and brother, also miners, were among the victims.

Selwyn M. Taylor, 42, was an engineer who knew the mine well. He arrived at Harwick hoping his expertise could save any of the miners facing an otherwise certain death. Taylor went into the mine with two other men and found Gunia alive on his first trip down. After rescuing Gunia, Taylor went back into the mine’s toxic atmosphere looking for other survivors but found none. Taylor and Daniel A. Lyle, 43, both died of asphyxiation during rescue attempts. Their efforts caught Andrew Carnegie’s attention and led to the Commission’s inception just three months after the disaster.

Gunia and Marshall’s mother, Ella, were siblings, and within the Marshall family, Gunia’s story was certainly well known, but it’s impossible to know whether this history had an effect on Marshall. All we can say for sure is that Marshall grew up knowing that but for the brave choice of a stranger to help Gunia, his uncle would have died in that mine, and that Marshall himself lived an exemplary life of service.

Marshall first served his country in the Navy through World War II and the Korean War and then served the people of Pittsburgh-suburb Fox Chapel as the police chief for more than 20 years. In between, he became a Carnegie Medal awardee when he intervened in a robbery on Dec. 22, 1953. Then a milk deliveryman, 27, Marshall was walking to a grocery store near his home in Indiana Township, Pa., to get the evening newspaper when he came across the store owner’s wife, Thelma E. Perry, 43, outside the store. According to a newspaper account of the robbery, she told Marshall, “There’s a man with a gun inside,” and offered him a .38-caliber revolver before heading back into the store.

Before entering himself, Marshall noticed that the gun was not loaded. He was nervous but ultimately chose to use the gun as a bluff. Inside, Marshall found the owner, Calvin L. Perry, 46 and his assailant struggling for control of a gun pointed toward the floor. The gun fired, and the bullet struck Perry in the hand before ricocheting and striking his wife in the leg. Marshall, who stood just 12 feet away from the men, pointed his unloaded weapon at the assailant and demanded that he drop his gun. The robber and an accomplice waiting outside both surrendered to Marshall.

Every hero faces a choice to risk his or her life in order to save another’s, and many factors can affect the choice to be a hero. The connection among Taylor, Lyle, and Marshall raises the possibility that a message of heroism can be spread and the culture of heroism can be nurtured, leading to more people choosing heroism when their moment of choice arrives. As Marshall considered the unloaded revolver, he may not have explicitly recalled the brave acts of Taylor and Lyle 50 years earlier, but his connection to this piece of history may have played a role in his life-long dedication to serving others, and may in turn have contributed to his heroic choice.

As the great-grandson of Adolph Gunia, I have a deep appreciation for the choice that Taylor made. Without it, my family simply would not exist. My wife and I honored this choice by giving our daughter the middle name “Taylor” when she was born six years ago. She doesn’t yet understand the significance of the name, but it ensures that the story will be a part of her upbringing, as well as that of her younger twin brothers. By keeping the connection to Taylor alive in our family, I hope that if any of us is ever faced with a choice like that faced by Taylor, Lyle, Marshall, and all of the other Carnegie Medal awardees, we will choose to be a hero too.