In the early afternoon of Monday, April 28, 1958, 34-year-old John J. Ryan and his Powell Valley Electric Cooperative colleague, 49-year-old Davis L. McNiel, left Jonesville, Virginia, in a Bell 47G-2 helicopter.

Pilot Ryan and McNiel, a utility manager, were surveying power lines that day, and while Ryan was stationed at the ‘copter’s controls during takeoffs, landings, and hovering for inspections, he was also teaching McNiel how to fly and would turn the controls over to him for training.

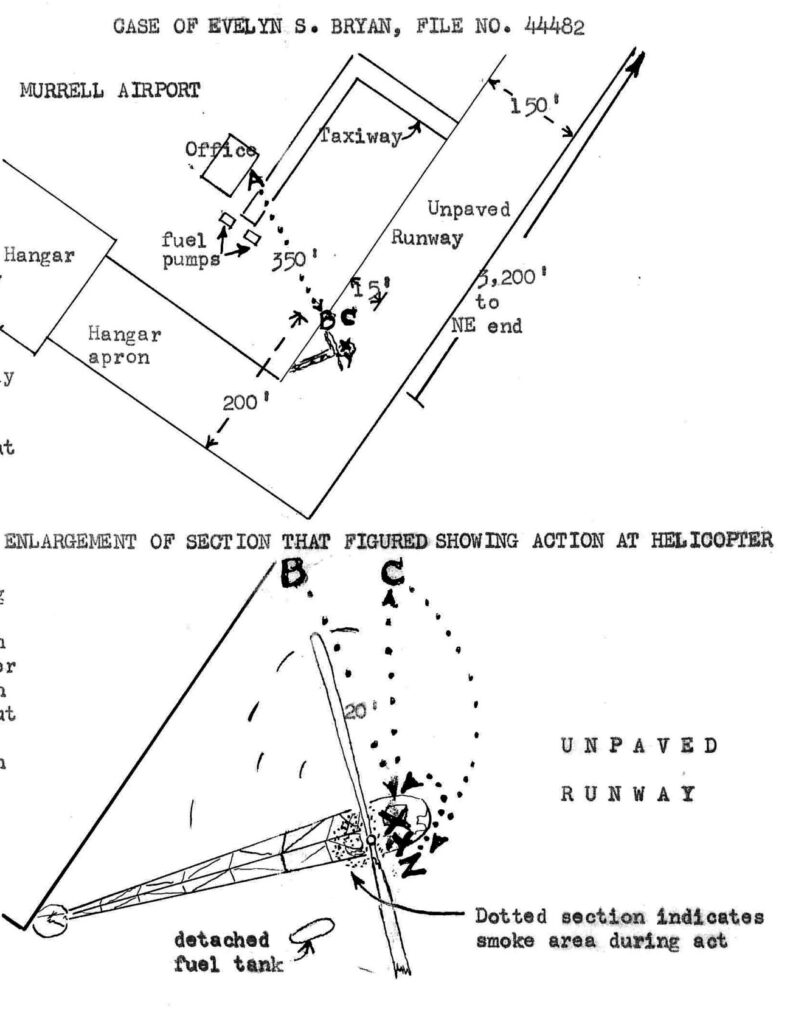

At 1:40 pm, near Morristown, Tennessee, they landed on the graded, unpaved runway at Murrell Airport for gas. There were two gallons of fuel left in the helicopter’s tank. The weather was fair and mild, with only a slight wind.

Evelyn S. Bryan, a 48-year-old flight instructor and operations partner at the airport, was the only employee on duty. She appeared from the office, a single-story frame structure, and went to the pumps to fill the two main and two auxiliary tanks of the helicopter with 51 gallons of fuel.

Two boys, Wayne Watkins, 13, and Gerald Carter, 16, were riding their bikes by the airport and had stopped to watch the helicopter land on the taxiway. They went to join Bryan near the doorway of the office to further admire the craft.

Ryan and McNiel re-entered the cockpit and readied themselves for takeoff. Ryan was seated on the left, in the pilot’s seat; McNiel sat on the right, ready to assist.

On the ascent, Ryan piloted the helicopter about 150 feet vertically above the runway. He then turned the controls over to McNiel who piloted the craft in a southwesterly direction about 200 feet, turning sharply and tilting the helicopter.

Ryan immediately took control and attempted to steady the craft, but it did not respond to his efforts. The helicopter descended to the runway, crashing on its right side with the engine still running and the main rotor blades running at full throttle.

The accident broke the helicopter’s skids, shattered its plexiglass bubble-canopy, destroyed the engine cooling fan, and bent the craft’s mast that supported the revolving rotor blades, creating friction in the helicopter’s mechanics resulting in an overheated engine. Fuel leaked from the helicopter, smoke issued from its engine, and as the rotor blades continued to hit the runway, the chopper wobbled continuously. The left door of the cockpit was heaved open.

As the blades continued rotating, one of them broke off about 8 feet from the mast, while the other remained intact and continued to rotate.

Inside, McNiel was believed to have died on impact, and Ryan was rendered unconscious. He had suffered a concussion, a broken back, and a broken right femur.

Bryan, witness to the crash, was dressed in a cotton blouse, wool scarf, and silk head scarf. She had extensive aircraft experience in general and had held her flying license for 14 years and a flight instructor’s license for 11 years. Additionally, she had just started learning to fly helicopters the previous month. Although she hadn’t flown the Bell 47 G-2 before, she had serviced other helicopters of the same model at Murrell Airport. From her familiarity with the model, she knew the location of the craft’s fuel tanks and where the engine switch could be turned off.

Bryan could see the engine was still on, causing the blades to rotate, which she later told Hero Fund investigator H.W. Eyman could potentially lead to an explosion.

She grabbed a carbon dioxide fire extinguisher from the office’s doorway and raced toward the helicopter, slowed only by an area of sticky mud on her route.

Wayne, one of the boys who stopped to admire the helicopter, followed her. Gerald remained near the office doorway.

Bryan lugged the fire extinguisher about 350 feet through the muck before reaching the edge of the runway. She continued toward the cockpit, where the rotor blades moved rapidly, raising and lowering the fuselage and cockpit as they hit the runway.

To the investigator, she relayed her fears that because the cockpit was wobbling, the clearance with which she had to work varied drastically. Despite her worry, Bryan threw the extinguisher to the runway and crawled toward the cockpit as the blades continued to spin overhead.

Then, as the craft continued to wobble, she entered the cockpit. Leaning over Ryan, she reached for the switch with her right hand and shut off the engine, halting movement of the blades.

As dense smoke continued to spread from the engine and the threat of fire or explosion loomed, Bryan withdrew herself from the cockpit and ran back to the fire extinguisher.

Wayne handed it to her and she ran back to the wreckage where she employed the CO2 foam on the engine area, cooling it down and dissipating the haze.

She could now assess the state of the two men. McNiel appeared to be dead. Ryan weakly groaned.

By now, Richard M. Morelock, a retired real estate professional and eyewitness to the accident, approached the wreckage. Others from the highway also made their way toward the scene.

“What happened to me?” muttered Ryan, who had regained partial consciousness, to Bryan.

Bryan explained the helicopter crashed, and she feared McNiel was dead.

Morelock and two other men reached the side of the cockpit and, with Bryan, tried to pull Ryan out of the cockpit. He yelled in agony. Bryan suggested they leave him in the aircraft until medical professionals arrived. Soon an ambulance reached the airport and medical personnel removed Ryan and McNiel from the wreckage and took them to Morristown Hospital where McNiel was pronounced dead.

Miraculously, none of the spilled gasoline ignited, and no explosion occurred.

After receiving emergency treatment, Ryan was transferred to a hospital in Knoxville, Tennessee, where he stayed for several months and underwent three operations.

During the Hero Fund’s investigation, Ryan was still under a physician’s care but almost completely recovered. After the accident and subsequent medical treatment, his right leg was 1.5 inches shorter than his left.

Bryan was not injured, but she did experience slight shock and was shaken up for a few days following the accident and her heroics.

Bryan shared with Eyman that she did consider the fact that she could lose her life – due to the leaking fuel, which could have started a fire or caused an explosion, and the revolving rotor blades, which could have crushed her as she entered the cockpit. However, she ignored this threat until she was able to turn off the engine and use the fire extinguisher to cool off the hot engine and eliminate the smoke engulfing the wreckage.

For her bravery, Bryan was awarded the Carnegie Medal and a $250 financial reward.

Bryan, later known as Evelyn Bryan Johnson, went on to fly until she was 97 years old.

When she died in 2012, the Los Angeles Times highlighted her incredible life and flying career.

She described learning to fly in 1944 as “love at first sight.”

At the time, she held the Guinness World Record for logging the most hours in the air for a female pilot – 57,635.4, which is equivalent to 6.5 years.

— Abby Brady, Communications Assistant/Archivist