U.S. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt wrote more than 8,500 columns that appeared in newspapers around the country from 1935 to 1962. Entitled “My Day,” Roosevelt wrote about whom she met, where she travelled, what she was reading, and how she went about dealing with the pressures of public life. Among the columns, she mentions Susan B. Anthony, King George IV, Gene Kelly, Willa Cather, and Carnegie heroes Guy E. Quinn and Bradford Gainer.

In her May 5, 1943, column she writes about receiving word that Quinn and Gainer were awarded the Carnegie Medal.

“I am happy that both these cases gained recognition,” she said. “I think that we should be grateful for the spirit which recognized that deeds of heroism should be acclaimed. I am sure that every time a man or his dependents receive such recognition, it is of value to the country.”

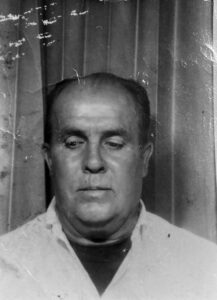

In the frigid temperatures of January, 1943, a fire started in a mine in Pursglove, West Virginia. Smoke drifted through the mine passages to areas where men were working, and Quinn, a 42-year-old mine foreman of Morgantown, West Virginia, instructed others to notify other groups of men to evacuate the mine. Quinn soon learned that a group of 11 men had not been warned of the fire, and he called for volunteers to help save the men from suffocating.

Joined by Gainer, 31, of Pursglove, and one other, Quinn walked more than 2,000 feet toward the fire through dense smoke to warn the men, whom they failed to find. Quinn collapsed from lack of oxygen. Gainer and the other man carried him toward safety, but ultimately had to leave him to summon help. Quinn and the other 11 men were removed from the mine later, all having died. Gainer suffered from the effects of the smoke and gas for two days after the incident, but he recovered.

Gainer and, posthumously, Quinn were awarded the Carnegie Medal April 30, 1943. The third man who assisted with the rescue did not receive the Medal. According to Hero Fund records, he was responsible for failing to notify the men originally, and Hero Fund requirements state that heroes must be free from responsibility in creating the danger.

A ceremony was held at the site of the Pursglove mine a month after the awarding, and Roosevelt and her husband attended.

“Here the ceremonies were held for the presentation of Carnegie Hero Fund Medals … two awards were made, one to a man’s family for his heroic death, and one to a man who came through alive,” she wrote. “It was very thrilling to be able to take part in these ceremonies.”

Quinn’s family received a monthly stipend of $65 until his widow, Anna Quinn, remarried in 1946. Gainer received $500 from the Commission, which he used to relocate his family to Ohio, according to his great-granddaughter Emma DiGiulio, who recently visited the Commission in Pittsburgh to learn more about Gainer.

Although Gainer’s descendants treasured his Carnegie Medal, they did not know that Eleanor Roosevelt had written about the patriarch until recently.

Christine DiGiulio, granddaughter to Gainer, who died in 1967, was researching her family tree in the wake of daughter Emma’s genetic test results, when she came across the columns.

“Everyone was really excited,” Christine recalled. “I woke up my husband at like 3 a.m. to tell him.”

Rose Sickafoose, daughter to Gainer and mother to Christine, is, perhaps, the most touched by Roosevelt’s mentions of her father. She called the Hero Fund to tell them about the discovery.

“My father was a kind, loving, family man, who loved God. He’s always been our hero, and we have always been so proud of him, but the fact that Eleanor Roosevelt took her time to recognize him – that’s truly giving him the recognition he deserves,” she said.

“What a great way to remember him.”

George Washington University has cataloged and indexed all of Roosevelt’s columns as part of the Columbian College of Arts and Sciences Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project. The columns “chronicle her development from awkward ‘diarist’ to skilled advocate for the New Deal, civil rights, the United Nations, and myriad other domestic and international concerns. In sum, ‘My Day’ offers a remarkable window into ER’s public and political life,” the website states.

— Jewels Phraner, editor