On January 13, 1982, cold temperatures and snow plagued the Washington, D.C., area so much so that, by the afternoon, businesses and schools had closed for the day. The great exodus from the city resulted in a major traffic jam.

Roger Olian, a 34-year-old sheet-metal worker for St. Elizabeth Hospital, and M.L. Skutnik III, 28, an office services assistant for the Congressional Budget Office, were among those trying to return to their suburban neighborhoods – Olian to Arlington, Virginia, and Skutnik to Lorton, Virginia.

By 4 p.m., Olian was stopped on the 14th Street Bridge as his car’s gas tank depleted and the battery waned. Snow continued to fall and the air temperature was about 25 degrees. Skutnik sat in another vehicle on the bridge, accompanied by four members of his carpool.

Meanwhile, Donald W. Usher, 31, chief pilot from Gambrills, Maryland, and Melvin E. Windsor, 41, rescue technician from Monrovia, Maryland, were stationed at the hangar of the Aviation Section of the U.S. Park Police, waiting for the winter storm to pass. Earlier in the day, as chief pilot, Usher decided that no routine flying would be permitted because of the inclement weather.

At Washington National Airport, now Ronald Reagan Airport, flight delays abounded. Air Florida Flight 90, which was headed for Fort Lauderdale, Florida, was scheduled for takeoff at 2:15 p.m., but weather delays and the process of de-icing the plane delayed departure until 4 p.m. Seventy-nine people were aboard the Boeing 737 jetliner.

Trouble prior to lift off did not end once the plane was airborne. Almost immediately, the 102,000-pound plane lost altitude. Less than a mile from the end of the runway, the jetliner crashed into the traffic- clogged 14th Street bridge, where it struck seven occupied vehicles. Four people were killed and four others were injured.

The plane descended past the damaged bridge wall and railing, breaking through the ice-covered Potomac River. The wreckage sunk in 25-feet of water. About 73 people aboard lost their lives.

In the next 20 to 30 minutes, the six survivors of the crash would be shown selflessness and bravery by four men who came to their aid in multiple ways from the ground and air. Kelly L. Duncan, stewardess, and passengers, Priscilla K. Tirado, Bert D. Hamilton, Joseph Stiley, Patricia Felch, and another man, surfaced amid remnants of the plane’s tail. They were surrounded by debris and sheets of ice about 120 feet from the Virginia bank of the Potomac River. The brutal cold crept into their bodies as they cried for help.

Back on the bridge, Olian learned of the crash from another motorist. Abandoning his car, he ran to the riverbank as the cries of the survivors sounded.

In a later interview for the centennial celebration of the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission, Olian said, “If I did nothing, I couldn’t have lived with myself. But I knew I could live with myself if I tried and failed, even if I died.”

On the snowy, rock-covered bank, about 60 individuals had gathered. Some of them were fashioning a makeshift line from rope, belts, battery cables, and pantyhose. They threw these improvised lines out to the victims, but the strands fell short.

Olian, seeing these futile efforts, wanted to give the survivors hope through action.

At 4:07 p.m., Olian descended the steep, 10-foot bank and entered the glacial water. People in the crowd handed him the end of one of the lines they assembled from rope, a plastic clothesline, and a battery jumper cable. He fixed the line to himself and waded into the freezing water dabbled with broken sheets of ice. Meanwhile, Skutnik’s party had learned of the crash, and arrived on the bank. They brought a length of rope, which was added to the line tethering Olian, who had made it to chest deep water.

Unable to swim, Olian used his arms to propel himself between ice slabs, climbing on top of the ice when directed by those watching his movements on the bank. Olian continued this laborious effort while shouting words of encouragement to the survivors of the plane crash.

Stiley, one of the six plane crash victims, later stated that seeing Olian gave him a “wonderful psychological feeling.”

On the bank, bystanders continued adding to the line as more supplies arrived. When Olian was halfway to the victims, the line snagged on a fragment of ice. By now, he had been in the water for 20 minutes. However, in an effort to free himself from the line, Olian pulled himself closer to shore. Then, as he directed, the crowd pulled and released the line. Olian was free to resume his trek toward the six survivors.

As Olian approached the men and women clinging to fragments of the plane, albeit focused, he became increasingly physically tired. The pieces of ice to which he could cling or climb onto became smaller and there was jet fuel seeping from the area of the crash.

At 4:20 p.m., the sound of a U.S. Park helicopter, piloted by Usher, gave Olian the reassurance he needed.

Eleven minutes earlier, Usher and Windsor received a radio call from headquarters notifying them of a possible plane crash in the area. Despite the current weather conditions and Usher’s previous no-fly edict, the men decided to respond to the call. The duo readied themselves and the chopper, a Bell 206, and were off by 4:16 p.m.

Poor visibility meant Usher kept visual reference through the helicopter’s floor windows, using the highway as a landmark to guide him to the scene. During the four-minute trip, Usher and Windsor stayed connected with each other and the U.S. Park Police headquarters over the radio.

Windsor noted the expanse of white snow below them. They encountered freezing rain and combated ice buildup on the windshield by running the heat at full capacity. A brief respite in snowfall, allowed them to see the destruction below, including the wrecked vehicles on the bridge and the debris poking out of the ice-covered river.

When the crowd saw the helicopter arrive on scene, they pulled Olian to safety. He was within about 10 feet of the victims. Near shore, he was taken to a heated ambulance, and later to the hospital.

Taking the chopper over the jetliner’s exposed tail, Usher and Windsor saw six victims clinging to the wreckage, submerged to their shoulders and necks.

Usher circled the scene to appraise the situation at low altitude. He had extensive experience as a pilot in Vietnam and had performed rescues on the Potomac while flying with the Park Service, but the current conditions presented new challenges.

Usher maneuvered the helicopter so the skids were above the plane debris, and Windsor dropped life jackets and the looped end of a secured line to the victims.

The noisy craft prevented Windsor from giving any verbal direction so when Duncan, the plane’s stewardess, took hold of the rope, she followed his motioning to put the line around her chest, under her arms. On Windsor’s call, Usher took the craft up, and delivered Duncan to the crowd on the bank, which included arriving firemen.

Skutnik’s group handed their rope to Windsor before Usher flew back to the wreckage.

Windsor secured the extra rope to the helicopter, and another line to a life ring. Hamilton took hold of the rope, and Stiley put his head through the life ring, while holding onto Tirado and Felch.

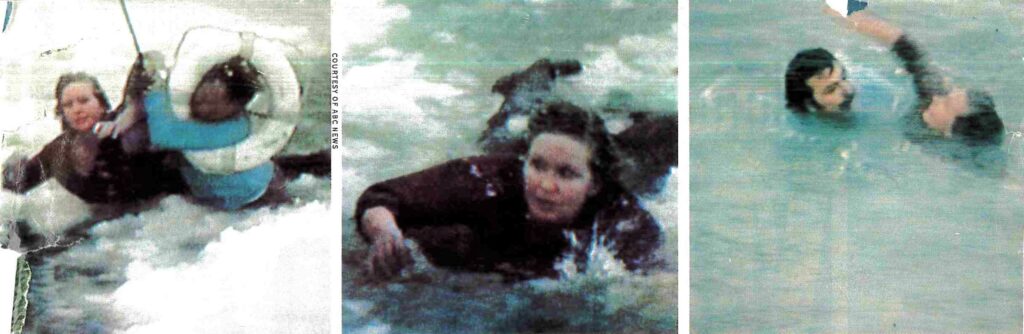

To maintain the helicopter’s equilibrium, Usher did not lift the victims from the water this time, but flew toward the bank, pulling them through the water. Twenty feet from the crash site, Felch fell back into the water and floated. Then, halfway to the bank, Tirado dropped onto a sheet of ice.

With Hamilton and Stiley still in tow, Usher continued to the water line where bystanders took hold of the men.

Three victims remained in the freezing water.

Usher returned to Tirado and dropped a life ring to her, but weak and blinded by jet fuel, she was unable to locate it. Windsor then maneuvered the line so the ring touched her and she grabbed hold of it. In the same manner as before, Usher towed Tirado through the water, to shore.

Twenty feet from the bank, Tirado lost hold on the ring.

After commotion on the bank, Skutnik, unable to watch Tirado’s suffering any longer, removed his boots and coat, and plunged into the frigid water. Although he had no experience in water rescues, his impulse to try outweighed any unfamiliarity he had, he later said.

Tirado was on her back and submerging when Skutnik reached her. He supported her and swam her toward a fireman who met them. Together they took Tirado to shore.

After the fact, Skutnik, interviewed by Time, reflected that his part in the rescue of Tirado was “Something I never thought I would do. Somebody had to go into the water.”

When Usher and Windsor saw that Tirado had been rescued successfully, they took the chopper back to Felch, who was bobbing near the wreckage, too exhausted to grab hold of a rope or life ring. Seeing her fatigue, Windsor unbuckled his seat belt and stood on the helicopter’s right skid, bracing himself against it. He stooped and seized Felch with one arm and supported the back of her head with the other.

Windsor directed Usher to turn the helicopter slightly so the skid would move under Felch and support a portion of her weight. At this point the right skid was under water and the other rested on a sheet of ice.

With Windsor and Felch delicately positioned on the skid, Usher returned to the bank, where rescue personnel received Felch. She was the last survivor out of the water, having endured 30 minutes of its numbing effects, after surviving a deadly plane crash.

The sixth victim, whose identity could not be conclusively established despite Hero Fund staff’s best efforts, was initially spotted by Usher and Windsor, bloodied and visibly injured; he had twice passed on the rope offered to him, instead passing it along to two of the five other victims. Usher and Windsor flew back to the wreckage to search for him. They scanned the area for several minutes but could not find the man who acted with selfless resolve.

“In a mass casualty, you’ll find people like him, but I’ve never seen one with that commitment,” Windsor reflected in an interview with Time magazine.

The five surviving victims were hospitalized and treated for hypothermia, internal injuries, and broken bones. All except Tirado were discharged a month later.

Olian took a 45-minute hot shower at the hospital, after which his body temperature rose to 97.5 degrees. He was sore for a few days and somewhat ill from what he suspected was ingested jet fuel. A month after the act he had yet to gain back full feeling in his extremities.

Skutnik was given a hot bath, but he was not detained at the hospital.

Usher and Windsor’s clothing was saturated with absorbed jet fuel fumes. They were not injured.

All four men were awarded the Carnegie Medal and monetary grants.

“I can’t begin to tell you how proud I am to be a recipient,” Usher stated in a letter to then-Hero Fund President Robert Off.

In addition to receiving the Carnegie Medal for civilian heroism, Olian, Skutnik, Usher, and Windsor received other recognition.

Skutnik was invited to sit with Mrs. Reagan during the State of the Union address, and after mention of his act by President Reagan, Skutnik received a standing ovation. He also received the Robert P. Connelly Medal of Service Beyond the Call of Duty award.

Olian gave $2,000 to the National Hospital in Arlington, Virginia.

In 2004, Windsor and his wife Maureen, attended the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission Centennial celebration at Carnegie Hall in Pittsburgh. The rescue on the Potomac was also featured in the accompanying video, ‘Heroes Among Us,’ and book ‘A Century of Heroes,’ both of which were produced for the occasion.

— Abby Brady, communications assistant/archivist