Aug. 12, 1955: Alarms sounded at about 6 p.m. in North Bay Village, a summer resort town situated on the western coast of the Chesapeake Bay near Fairhaven, Md. Volunteer firemen and local residents responded to the beach after a 22-year-old woman clinging to a piece of wood was pushed toward shore.

“I’m one of 27,” the woman told a North Bay Village man who had waded out into the ocean to assist her to safety, according to an Aug. 13, 1955, edition of Washington, D.C.-based newspaper The Evening Star.

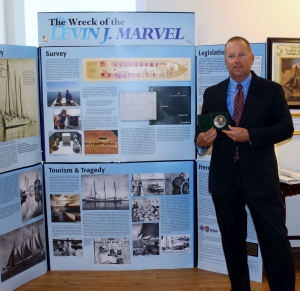

The woman was one of 23 passengers and four crewmen aboard the three-masted schooner Levin J. Marvel, which was about 128 feet long and weighed 183 tons. It had capsized five hours earlier in water north of the village during Hurricane Connie.

The sinking of the Marvel remains one of the worst disasters in the history of the bay, according to a 2003 article on Washingtonian.com. Fourteen of the 27 aboard the schooner died. Seven passengers clinging to debris from the wreckage made it to close to shore, where residents assisted them onto the beach. The remaining six victims were rescued by two brave men using a small wooden boat after they arrived at the scene to “lend a hand,” according to the Star article.

Aug. 12, 2015: The Bayside History Museum of North Beach, Md., commemorated the 60th anniversary of the Marvel shipwreck in a program at the North Beach Volunteer Fire Department. The event, attended by 380, celebrated the heroes, including William K. MacWilliams, Sr., 31, and his best friend, George L. Kellam, Jr., 28, who emerged that night to assist the shipwreck victims.

It was in heavy rain with 25-m.p.h. winds gusting up to 57 m.p.h. and waves as high as 12 feet that Kellam spotted someone waving a bright yellow hat from a duck blind some 1,000 feet from shore. He and MacWilliams looked for a boat and found a 12-foot-long wooden vessel with an outboard motor, but the motor had no gasoline. The men siphoned less than one-tenth of a gallon from a nearby automobile and added it to the boat’s tank before wading and towing the boat about 100 feet into the water. They were not wearing life jackets, and there were no life preservers on board.

Starting the engine, MacWilliams piloted the boat while Kellam bailed the rain water collecting inside it. In order to avoid the largest waves, MacWilliams took the boat over a zig-zag course. He later told the Commission’s case investigator that he was fearful that water repeatedly splashing over the engine would drown it or that a large wave would swamp the boat and capsize it.

When the men got to the blind and learned that six people had taken shelter there, MacWilliams was “chagrined,” according to the case report. He thought they had enough gasoline for maybe two trips, but he also knew that he could only take two people at a time or the boat would sink.

MacWilliams asked for the weakest first, and a female nurse, 33, and a male deckhand, 17, came to the doorway of the blind. As MacWilliams attempted to get the boat in position, a wave forced it into a piling, creating a deep dent in the boat’s bow, but the hull held. Kellam assisted the nurse and deckhand into the boat, and MacWilliams piloted the craft back toward shore. Despite bailing by Kellam, the deckhand, and MacWilliams—using his free hand—water in the boat grew deeper.

At a point about 150 feet from the beach, MacWilliams told the two victims to jump from the boat, as he felt confident that those on shore would wade out to help them in. Further, he didn’t want to take the time to get closer to the beach, as nightfall was approaching.

MacWilliams and Kellam returned to the duck blind to retrieve a housewife, 31, and a female copywriter, 35, next. On the return to shore, the rescuers discussed beaching the boat to empty it of water, but MacWilliams decided they didn’t have time. The housewife and copywriter jumped out at the same point as the others, and MacWilliams turned the boat for the final trip to collect the remaining victims, a male engineer, 32, and the schooner’s captain, 39. Water inside the boat continued to accumulate on the final trip, and as MacWilliams piloted onto the beach, a wave drowned the engine. About 15 minutes later, the duck blind collapsed.

On Oct. 26, 1956, MacWilliams and Kellam were each awarded a Carnegie Medal and $500 for their actions, the Commission having first heard of the rescue from the rescued copywriter, Nancy S. Madden. “I sincerely believe their courage merits highest recognition to these two men,” she wrote to the Hero Fund six days after the rescue. “The duck blind would not last long, we were sure. But we did not think anyone could possibly reach us in time.”—Julia Panian, Case Investigator

Return to imPULSE index.

See PDF of this issue.