On the warm evening of May 19, 1967, 23-year-old mother Toni Diffie fastened her 3-year-old daughter Ginger Lee into a canvas car seat that hung from the backrest of the family’s 1965 Ford pickup truck and drive toward the local Bisbee, Arizona, Circle-K market in search of some reading material.

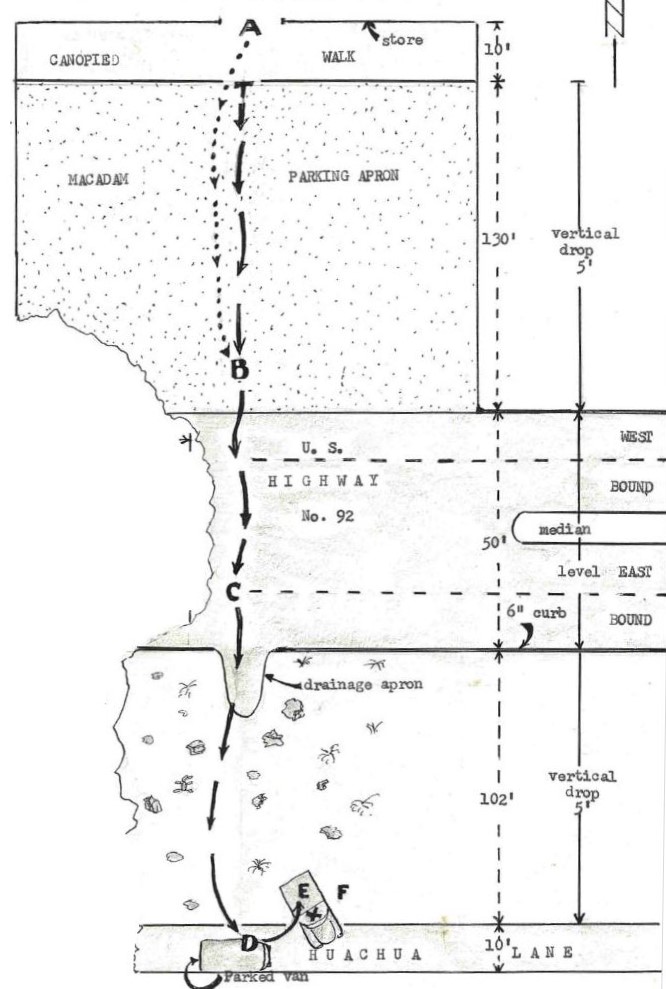

Because it was dinner-time, traffic on U.S. Highway 92 was light. The four-lane, east-west highway had no median between the two lanes in each direction; a 6-inch curb flanked the southern edge of the highway, separating the Circle-K parking lot from traffic.

When Diffie arrived at the grocery store, she parked the truck facing north, opposite the market’s entrance. Yielding to the incline, Diffie engaged the hand brake and placed the truck in a forward gear.

She entered the market, empty of any customers, and nodded to the store clerk, 27-year-old Billie Jean Power, who manned the only check out counter.

While Diffie perused the magazine selection, Power glanced through the front door and noticed little Ginger Lee in her car seat before turning her attention back to the task at hand.

The next time Power glanced up, the truck was inching backward.

“Your truck’s running away!” Power shouted at Diffie as she sprinted from the counter to the main entrance, in pursuit of the runaway truck gaining momentum in reverse.

In correspondence with Hero Fund Investigator H.W. Eyman, Power relayed her plan to jump onto the truck’s running board, reach into the cab, and pull on its hand brake to stop the vehicle.

As she chased the runaway truck, Power spotted a sedan. The car, driven by Samuel Sorich, Jr., 31, employment agent, approached in the westbound lane of U.S. 92.

During his eyewitness interview, Sorich stated that he believed there was a driver inside the truck and that Power was chasing a customer who had forgotten their purchase.

Power overtook the truck, which was moving at about 10 m.p.h., at a point when it was only 10 feet north of the highway. Just as she had planned, she leapt onto the running board facing toward the truck’s engine, reached through the open window with her right hand, and forcefully pulled the handbrake; it had no effect and the truck moved onto the highway.

Sorich slowed to avoid the truck. As Power maintained her hold on the side of the truck, and looked behind her to see what else was in the path of the backing truck, she spotted a small drainage apron on the other side of the highway. In her interview with Eyman, Power said she feared the truck would topple over when it came into contact with the ditch.

Releasing her hold on the faulty hand brake, she grasped the steering wheel with both hands, turning it hard, but Power was too late, and the truck’s passenger-side wheels wobbled over the apron.

Miraculously the truck remained upright, and Power held her position on the running board with Ginger Lee in her car seat.

After avoiding initial disaster, Power noticed a van parked on Huachuca Lane, a road made up of sand and clay that was scattered with jagged stones and boulders as much as a foot thick, clumps of sage, and the occasional cacti. Between the level highway and adjacent Huachuca Lane, there was a 5-foot vertical drop, and the truck was gaining momentum.

Power immediately pulled on the wheel to steer clear of the parked van. At a speed of between 15 and 20 m.p.h. the left side of the cab hit the front of the van’s fender, crushing Power’s pelvis in between the two vehicles while her upper body remained inside the truck.

Following impact, the pickup truck came to rest about 15 feet east and slightly north of the parked van.

Power fell flat on her back in pain. She was badly injured but remained conscious. Ginger Lee was uninjured but crying from all the action.

Sorich had witnessed the crash and quickly parked his car in the Circle-K parking lot. He ran to Diffie, who remained paralyzed in fright at the front of the store, before he sprinted to Power.

A neighbor on Huachuca Lane, Terrell Davis, heard the commotion from his living room and ran outside to render aid.

“I think my pelvis is fractured,” said Power while wincing and insisting he not move her.

Davis returned to his home and called for police and an ambulance.

By then, Sorich and Diffie had reached the scene, and Diffie removed Ginger Lee from her car seat.

Sorich, Davis, and Diffie remained with Power until emergency responders arrived.

At the hospital, Power’s injuries were detailed: her pelvis was fractured in seven places, her spine and left hip were fractured, and her bladder was ruptured.

She was in critical condition for seven days and remained in the hospital for nine more weeks. At the time of the Hero Fund’s investigation, she was recovering at home, primarily using a wheel chair. On the day of Eyman’s visit, Power had begun using a walker.

When Eyman inquired of the riskiness of her act, Power stated that at the beginning she only thought of the child, Ginger Lee. However, she said, fear for her life increased when the truck moved onto the highway where it would potentially strike another vehicle and her terror escalated as she failed to gain control over the truck.

Power and her husband Michael Power then had four children. He worked as a truck driver and the family owned a cattle ranch in Warren, Arizona. Arizona Workmen’s Compensation covered a portion of the wages Power lost as she recovered at home. In addition to the Carnegie Medal and $750, the Hero Fund granted her another $400 while she recovered and was unable to work.

— Abby Brady, operations and outreach assistant/archivist