It was 1973. Peter S. Norman, a 42-year-old miner from New Denver, British Columbia, was working 0.9 miles underground, deep in a Silmonac mine. There in a tunnel, about 8 feet wide and 10 feet tall, it was dark and dusty.

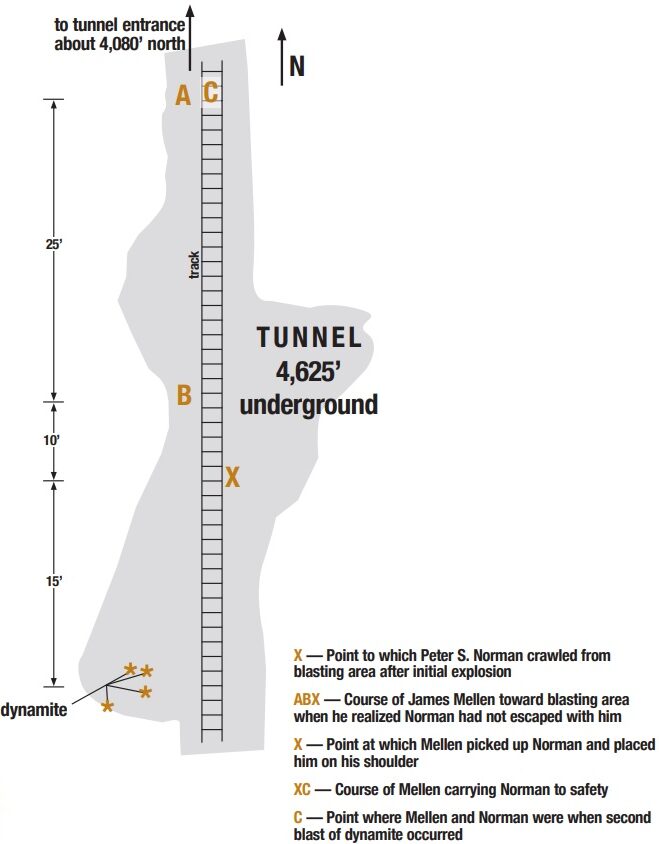

A narrow-gauge track for minecarts was situated in the middle of the tunnel. Other than the light from his headlamp, which allowed for 25 feet of visibility, it was pitch black.

The Silmonac mine, about 2 miles west of Sandon, British Columbia, was dug into the Selkirk Mountains. The tunnels carved in rock were mined for silver, lead, and zinc. At its peak production in 1971, 135 tons of minerals were harvested a day.

On May 24, Norman was tasked with using dynamite to clear out an area of the mine that would eventually be used for equipment storage.

Norman drilled 18-inch holes into four mounds that ranged from 1.5 to 2 feet high. He placed full sticks of dynamite in the largest mound and half-sticks in the other three. Then, starting with the farthest stick, he started to light them. Each stick of dynamite included a 3-foot long fuse, which gave Norman two minutes and six seconds to light the remaining three fuses and jog 50 feet to clear the area.

The next two fuses lit without difficulty, but the fourth and final fuse was wet.

Norman went to his hands and knees and continued to try to light the fuse.

James Mellen, a 35-year-old miner of Silverton, was about 15 feet from Norman.

Seeing Norman struggling with the last fuse, Mellen asked him if there was a problem.

“The last fuse won’t light,” Norman said.

Mellen pulled some matches from his pocket and was approaching Norman when the first charge exploded.

Norman flew 8 feet northeast. He lost his leather helmet and headlamp. He suffered a broken arm along with severe cuts.

Mellen was knocked about 6 feet.

A third man, Duffy Turner, who was also nearby, was thrown backward.

Debris that included pieces of rock larger than a softball rained down on them, and smoke and dust filled the air, reducing visibility to about 10 feet with headlamps.

Mellen managed to get to his feet and immediately ran north, knowing that two additional fuses had been lit. He shouted to Turner to clear the area.

Both men fled the blast area but paused and looked back for Norman. They could not see him or the light from his headlamp.

“Although he thought that Norman probably was dead,” Hero Fund investigator Walter Rutkowski was told, Mellen ran back to look for the miner despite the knowing that more blasts were coming.

Turner remained north of the explosion and watched Mellen disappear into the darkness.

The blast had filled Norman’s mouth with dirt, so he could not call for help. He managed to pull himself to a standing position when Mellen’s light shone on him.

Now, knowing Norman was alive, Mellen decided to help his co-worker escape from the impending blasts.

Mellen was described as being in, “excellent health and physical condition,” according to Rutkowski’s investigation. He had helped rescue a miner from a cave-in 14 years earlier.

With no equipment or anyone else in the tunnel, Mellen relied on his strength alone and hoisted Norman onto his shoulders.

The miner made his way back north while carrying Norman, “with thoughts of possible risk to his life since he knew there were other blasts impending…thinking only of getting as far away as quickly as possible,” Rutkowski noted in his report.

As Mellen continued 50 feet from the blast area with Norman, the second charge went off a minute after the first, but they had already fled far enough; neither man was affected by the blast or any of the significant debris.

Mellen kept on toward the exit when the third explosion occurred half a minute later, by which time both men were 100 feet away and safe. All in all, Mellen carried Norman more than 300 feet.

Mellen told Rutkowski that he did feel like he risked his life. Had he not moved fast enough, he could have been knocked down by the subsequent blasts or hit by debris.

Following the incident, Norman was hospitalized for two weeks as a result of his injuries and recuperated for three months before returning to work. He also had his blasting license revoked due to violated safety standards.

Mellen remained uninjured from the incident.

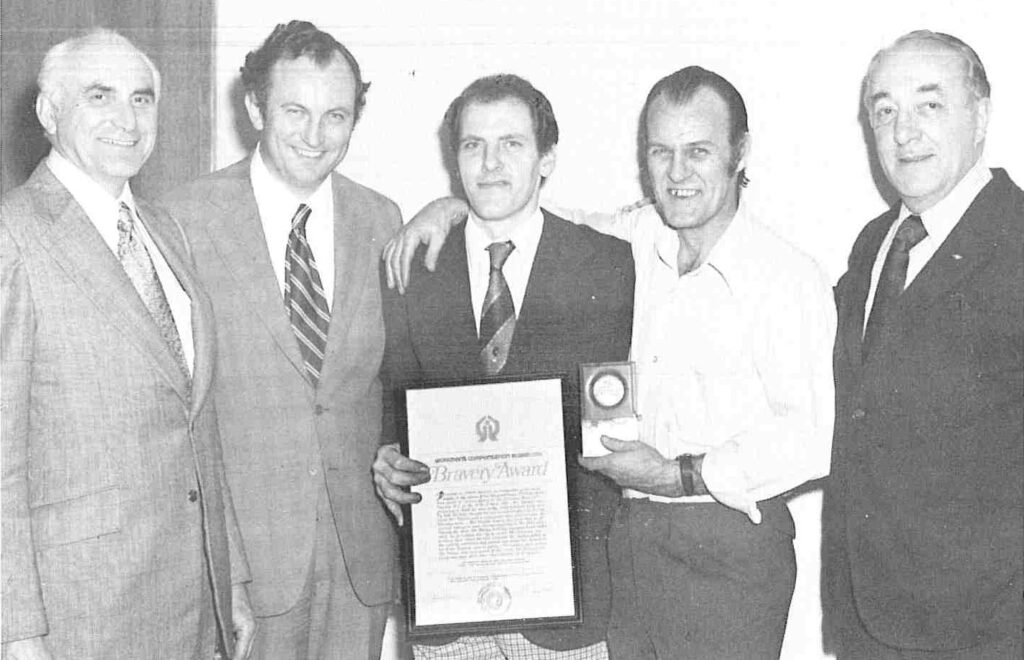

At the time of the Hero Fund investigation, he was married and had three children, a 17-year-old stepdaughter and two young children, ages 4 and 5. For putting his life at risk and his actions saving Norman from the impending explosions, Mellen was recognized with the Carnegie Medal along with receiving a silver medal from the Workmen’s Compensation Board and a gold medal from the Canadian Institute of Mines.

He told Rutkowski that he would use the Hero Fund grant money to visit his parents in England.

— Griffin Erdely, communications intern