tallest peak in the Squaw Valley Sierra Nevadas. Photo courtesy of The Outbound Collective.

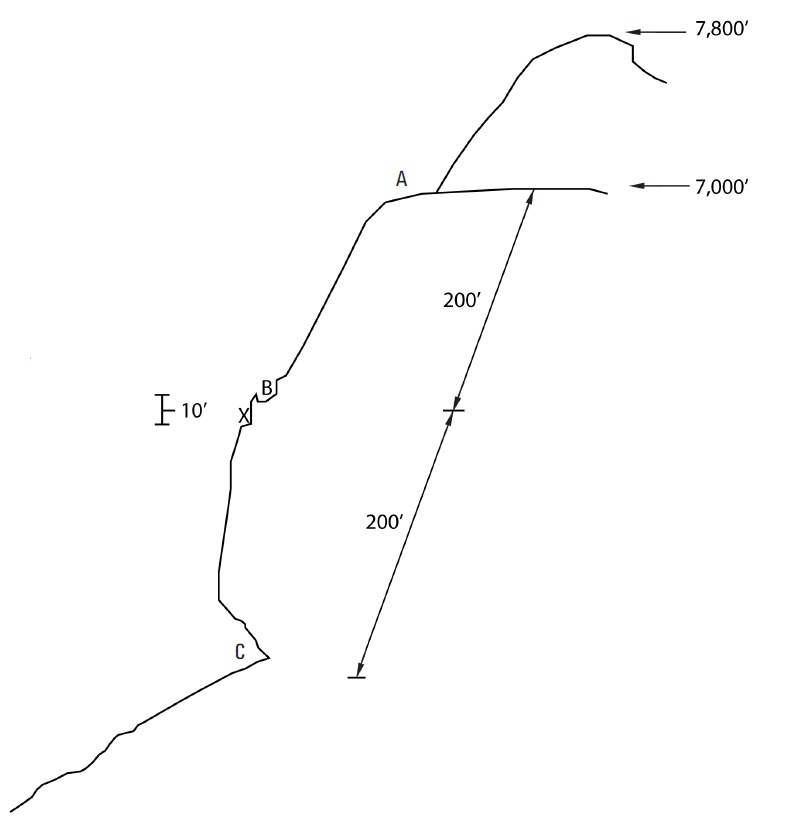

On the evening of July 7, 1965, 18-year-old Clayton E. Toensing was descending the steep face of a 430-foot cliff with two younger teenagers, when he lost his footing, fell 10 feet to a ledge, only a foot wide, and then desperately clung to a 3-foot scrub pine tree to avoid falling an additional 200 feet.

Moments earlier the 15-year-old boy with Toensing had also fallen about 260 feet, fracturing both wrists and his leg.

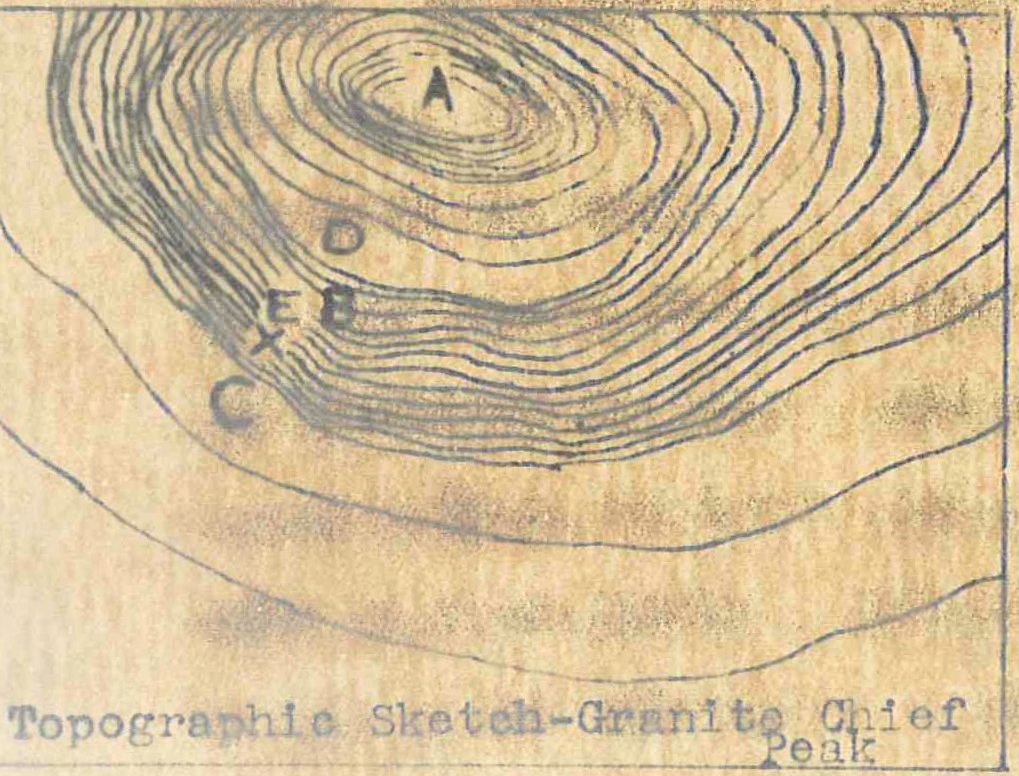

The three teens had hiked up to the top of the cliff on the northeast side of Granite Chief Peak in Squaw Valley, Calif.

As they had descended the cliff, they slid occasionally, but had all managed to maintain their footing by squatting and using their hands, until both male teens fell.

The 14-year-old girl continued to descend until she got down to the base of the cliff and notified emergency responders.

In interviews conducted by Hero Fund case investigator Ronald E. Swartzlander, Toensing revealed he was frozen in fear on that ledge, certain he would fall.

Howard D. Hill, 36, and Kenneth W. Terry, 41, both of Tahoe City, Calif., were alerted by a commotion of fire and rescue trucks, which they followed to the scene.

By then others had reached the 15-year-old boy, and a ranger and state park fireman spotted Toensing on the ledge. Toting a 200-foot-long rope with them, they made their way to the top of the cliff, but the rope wasn’t long enough to reach Toensing.

Hill and Terry could see the young man clinging precariously to the small tree and concluded that he was in danger of falling to his death.

By now, it was dusk, and Toensing had been on the ledge for about 80 minutes.

Swartzlander stated that neither man had mountain climbing training or experience. In the case file, he noted that Hill was unfamiliar with the rugged terrain.

Although darkness was near, Hill and Terry made their way up the backside of the cliff and reached its top in half an hour, taking with them a rope 250 feet long. The rope was partially weakened by a splice in its middle.

At the top of the cliff, the ranger and fireman secured their rope to a dead pine tree and prepared for the ranger to descend to Toensing.

Hill and Terry joined the effort and attached their rope to the one tied to the tree.

While Terry and the ranger held the rope and let it out as needed, Hill descended to the upper ledge, but from there, Hill was unable to see Toensing.

He shouted to him. Toensing replied weakly, and Hill encouraged him to remain calm.

While they spoke, Terry descended on the rope, which the ranger held firm. As Terry lowered himself, some small loose rocks fell toward Hill. Twenty minutes later, Terry joined Hill on the ledge.

“Hold my legs,” Hill instructed Terry as he looked over the edge to determine Toensing’s location.

Terry sat down with his feet braced against a lip at the edge of the ledge and grasped Hill’s legs.

Hill moved to the edge, peered over it, and saw Toensing below.

In an effort to lower Hill farther, Terry moved forward in a sitting position, bending his knees as he kept his feet against the lip for leverage. Terry’s forward movement allowed Hill to extend himself over the edge to his waist.

Hill relayed to Swartzlander that while he could reach Toensing’s wrists, he was uncertain he’d be able to pull the young man up from his current angle.

Hill moved back to the upper ledge where he and Terry contemplated their next move.

Hill and Terry pulled down the rope so that its full length hung from the tree. Hill formed a loop with a slipknot at one end. Now, they were prepared to retrieve Toensing.

Assuming their positions, Terry grasped Hill’s legs as he did before, and Hill, laid on his stomach, his upper body extending over the edge.

Hill directed Toensing to move one hand at a time from the tree he grasped. Toensing obliged and Hill dropped the looped rope over him to around his chest.

Terry pulled up all slack in the rope while still holding Hill by the feet. Both he and Hill acted with an abundance of caution.

With his upper half dangling over the edge, Hill held to the rope with one hand and grasped Toensing’s right wrist with the other. Hill inched his body backward on the ledge while maintaining his hold on Toensing, who was in shock and not able to help support himself.

As soon as Hill was squarely back on the ledge, Terry released his hold on his legs and pulled on the rope with both hands.Working methodically, they hoisted Toensing the 10 feet to the upper ledge in 20 minutes.

Hill and Terry were winded by their vigorous efforts and rested for about 15 minutes before using the rope to fashion a sling about Toensing, and lower him to the bottom of the cliff where the ranger and officer were waiting.

In total darkness Hill began descending the rope hand over hand.

About halfway between the ledge and the bottom, he felt a splice where the rope had thinned and was momentarily panic-stricken.

Hill indicated to Swartzlander that he feared the rope might break as he continued to lower himself, and that his worry grew when he reached the concave part of the cliff, where he was unable to obtain footing.

However, he did explain that he was comforted by the sound of voices heard below.

Hill opted not to tell Terry about the portion of weakened rope so as not to scare him.

Terry descended in the same manner, hand over hand.

At the concave point, Terry also became frightened because he could not find his footing.

He shouted to Hill, who assured him that he was close to the base of the cliff.

Shortly, Terry made it to the bottom.

After ensuring Toensing had reached safety, it took the men an hour and a half to make their descent—half of which was done in total darkness.

For the majority of their descent, Hill and Terry maintained secure footing against the cliff.

However, for the final 60 feet, they were tasked with navigating the bowl-shaped portion of earth, which made it nearly impossible for them to retain stable footing.

Toensing was treated for shock and recovered. The15-year-old boy was hospitalized for injuries and he too recovered. The girl was not injured.

Hill and Terry had torn their clothing during the rescue. Their hands were red and sore, but did not blister. Their scratches healed in a few days.

When asked about risk, Hill indicated that he was concerned for his life multiple times — first when he was lifting Toensing to the upper ledge and feared he might slip. His dread increased when he was descending the rope and arrived at the splice point, and finally when navigating the hollow portion of the cliff.

Terry shared Hill’s fear of the thinning rope and concave area of the cliff. In addition, Terry worried Hill would fall and pull him over the

edge as he held his feet.

The Carnegie Hero Fund Commission awarded Hill and Terry silver medals and $750 each. Presentation of the silver medal,

which ceased in 1979, indicated that the awardees repeatedly risked their lives in the persistent performance of their heroic act.

“I received the Carnegie Medal today, and I am more than pleased,” Hill wrote to the Commission in 1967. “Not only with its beauty, but its significance. I also wish to thank you for the cash award. It has helped my family and myself tremendously. Thank you seems to me a small way to show my appreciation, but it is with my deepest gratitude.”

The men also received a silver medal and $1000 each from their employer, The Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Co., of Sacramento, Calif.

As reported by case investigator Swartzlander, Hill put aside a majority of his award money for the education of his children. Similarly, Terry applied the money toward his oldest daughter’s first year of college and saved the rest for his children’s future educational expenses.

— Abby Brady, operations and outreach assistant/archivist