On the cool morning of Sept. 7, 1913, at California’s Susanville Hospital, a father and son were residing in adjacent rooms. William D. Minckler, Sr., a 62-year-old civil engineer, was suffering from palindromic rheumatism, which caused inflammation and made it difficult to walk. His son, William D. Minckler, Jr., 25, civil engineer’s assistant, had been in a motorcycle accident and was experiencing a severe concussion that caused delusions and outbursts of violence. He had been in the hospital for six weeks and was not expected to live.

Lillian M. Coburn, 42, matron of the hospital, requested an orderly fill and light the coal oil stove in the elder Minckler’s room while she prepared to give him a bath.

She stepped out of the room located in the northwest corner of the hospital’s one-story wing to gather towels from a linen closet and warm water from the bathroom.

During this brief absence, Coburn heard a popping noise. When she turned back to Minckler’s room, she saw flames erupting from the top of the door.

The stove, containing about one gallon of oil, had exploded and caught fire. Flames were quickly dispersed throughout the hospital’s pine structure, and there were no fire extinguishers available to provide relief. The weather that day was fair and there wasn’t any breeze. Hero Fund Special Agent M.H. Floto presented these details about the hospital’s structure, weather conditions, and specific risk factors Coburn faced, so Hero Fund officials who would review Coburn’s qualifications for the Carnegie Medal had no doubt of the dangers she faced.

Minkler, lethargic from the medicine he had been given, remained asleep. In the room adjacent to the east, his son, William, was oblivious to the peril. It was clear that father and son were in danger of being burned to death.

In addition to the Mincklers, there were at least 15 other patients in the building, including four or five who were considered by staff to be practically helpless.

J.H. Platt, a patient who was faring well, shared a room with William and had been keeping an eye on him while Coburn tended to other duties. He exited to the hallway where Coburn had just witnessed the eruption of flames.

“What can I do?” Platt inquired, wringing his hands.

“Save yourself,” Coburn directed. Platt ran for safety.

In the regulation linen uniform of a trained nurse, Coburn, who was assiduously familiar with the hospital, ran into Minkler’s room. Flames covered the walls and ceiling and the hospital bedding was ablaze. Fire licked Minckler’s head and had spread to his head and shoulders.

Coburn pulled Minckler from his bed, put a bath towel over his head, and walked him into the hall. She pushed him ahead of her until they reached William’s door. Here, she instructed him to stay close to the wall and pushed him in the direction of safety.

By now, fire had spread to the west end of the hall. Flames and upper segments of the walls burned easily as they were full of a cotton material for insulation and covered with wallpaper. Heavy smoke permeated the hallway. A draft from an open transom window pushed the flames east.

Coburn entered William’s room. He lay in his hospital bed as flames were beginning to encroach the upper portion of the west wall.

Coburn quickly lifted William in her arms. She attempted to push him out through the first-floor window, but in his concussed state, William kicked and struggled, and Coburn was thrown to the floor. She toiled for a few more minutes before Coburn decided on another method. Using a bath towel, she twisted it around William’s neck and dragged him into the hall.

Here, Coburn found Minckler had not gone to safety and was still standing along the north wall, dazed and mumbling to himself.

Smoke weighed down on them ominously and the draft pushed flames to the ceiling of William’s room. As conditions worsened, the two other nurses on duty removed patients out through windows.

“Keep your mouth closed,” Coburn instructed a murmuring Minkler, before she pushed him forward with one arm and dragged William with the other.

A sharp pain pinged Coburn’s neck, shoulders, and arms — her clothes had caught fire.

Battling the excruciating sensations, and struggling to maintain control of the disillusioned men, Coburn’s remained steadfast in her conviction to get her patients to safety.

She continued toward the kitchen, but the screen door offering exit was locked.

Undeterred, Coburn maintained her hold on the father and son, making her way to the dining room and then out to a screened porch. A man who was never identified met Coburn at the door and threw a coat around her shoulders to extinguish the fire burning on her uniform.

About this time, Coburn became aware that her hair was also burning. She had been wearing a celluloid comb, a decorative hair piece made of synthetic materials prone to combustion, and it had ignited.

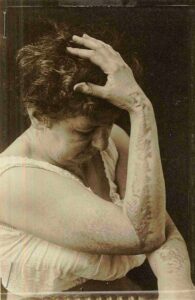

Coburn’s injuries included third-degree and minor burns on her neck, shoulders, arms, left ear, and a portion of her cheeks, and smoke inhalation. Case investigator Floto noted that she had undergone continuous treatment after the incident.

There was no doubt Coburn had risked her life to an extraordinary degree to save the Mincklers, and well beyond her professional responsibility, as Floto’s report to the Commission clearly proved.

Coburn was awarded the silver Carnegie medal and a $1,100 grant. From 1914-1919, the Hero Fund supported Coburn and her son with beneficiary payments.

A Letter received by the Hero Fund on Nov. 28, 1913, nominating Nurse Lillian M. Coburn for a Carnegie Medal. Mrs. R.W.J Garner provided details on the risk Coburn undertook to save William D. Minckler Jr., and Sr., from burning after a coal stove caught fire in the elder Minckler’s hospital room at Susanville (California) Hospital. She wrote, “With her arms, one around each she dragged these two thru the flames to safety, at terrible cost to herself for she received burns from the effect of which, it is not likely she will ever fully recover.”

— Abby Brady, operations and outreach assistant/archivist