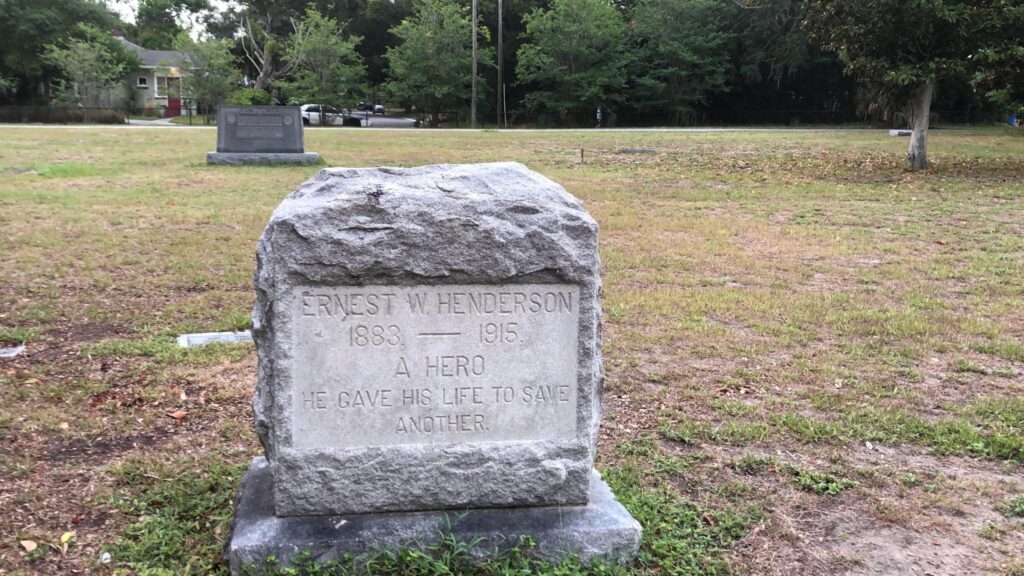

A Carnegie hero’s headstone recently caught the eye of a Florida resident, who set out to learn more about Ernest W. Henderson, his 1915 drowning, and his family.

At Royal Palm South Cemetery in St. Petersburg, Florida, one side of a grave marker bears the name of Henderson, who died on January 30, 1915, and the opposite has that of his wife, Claire, who died just shy of nine months later. Henderson’s heroism previously was described in an Impulse article (Issue 62, Summer 2020) that highlighted another rescuer, Lucy G. Branham, a teacher who later forged a reputation as a suffragist.

Tyler Travers, of Pinellas County, found the previous Impulse story after seeing the headstone, which identified the 31-year-old Henderson as a hero who “gave his life to save another.” The brief epitaph in what Travers labeled as a “forgotten cemetery in an urban area” sparked Travers to “seek to learn anything I can get my hands on to better understand.”

In wanting to discover more about Henderson, Travers’s curiosity helps us reveal some additional details about the community campaign to assist the brave painter’s widow.

The calamity began when a 26-year-old teacher, Dema T. Nelson, and a 17-year-old student, Izola Aslin, were struggling in the waters of Coffee Pot Bayou near their St. Petersburg school and shouted for help. Another student, Ruth E. McNeely, swam out to Nelson and Izola. After some difficulty, McNeely helped Izola to a man, who guided her to shallow water. Henderson dived off a deck and swam to Nelson, but they then separated and a third man responded and Henderson grabbed onto him. When they broke apart, Henderson then went below the surface and ultimately drowned. Branham, along with the third man, helped rescue Nelson.

In the aftermath, faculty at the school, Southland Seminary, held a benefit to help raise money for Claire Henderson and her three children, according to a Feb. 7, 1915, article in The Florida Metropolis newspaper in Jacksonville. Nelson, listed as being in charge of the seminary’s “school of expression,” was among those who participated, described as “the star” who gave “several readings that were pleasing.”

The benefit was part of a movement to collect at least $5,000 for Henderson’s survivors. Another story, posted on Henderson’s page at findagrave.com, outlined a push by Charles R. Hall, a “real estate man,” to help Claire Henderson send her children to school.

“Ernest Henderson gave his life in a heroic way,” the story in an unidentified newspaper quoted Hall. “The people of this city should think of what it means to his family to be without a head. The least we can do is to make a money compensation to Mrs. Henderson in order that she may educate her children. I am doing everything in my power to raise this fund and will co-operate with all interested.”

But before the year was over, Henderson’s children were orphans. His young widow, 30, died of blood poisoning on Oct. 22, 1915, after an illness lasting several days, according to a copy of the death certificate that Travers located and shared.

The Hero Fund’s board approved Henderson’s posthumous award – and medals to Branham and McNeely – at their meeting seven days later. The Hero Fund provided $40 – equivalent to about $1,200 today — in monthly support to the trustee of the three children until they reached “working age,” according to Hero Fund records.

— Chris Foreman, Assistant Investigations Manager