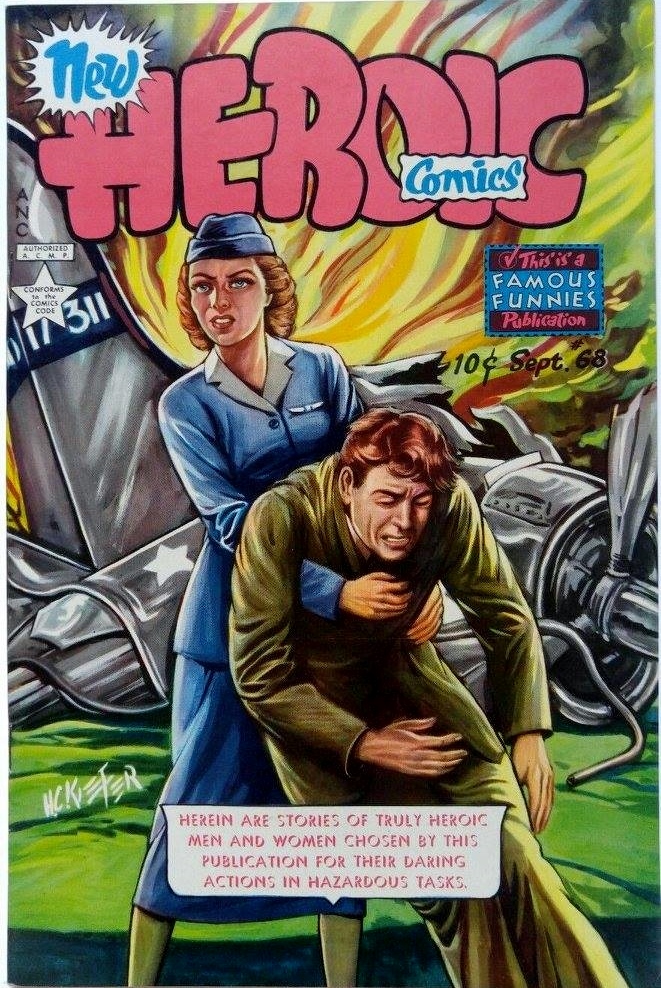

Those who learn about the life and death of Carnegie Hero Mary Frances Housley seem to get invested. From a 2007 high school A.P. U.S. History class at Housley’s alma mater to a now-closed Eastern Color Printing Company that featured her in a 1951 comic book, those who rediscover Housley and her heroism want to make sure her story continues to be told.

That’s why a Knoxville, Tenn., health science teacher petitioned the city of Knoxville to name a bridge after Housley.

“Aside from honoring her and her sacrifice, I also wanted to restart the conversation about her,” said Chris Hammond. “I wanted to bring her story, the story of her sacrifice back to life, back up to the surface.”

On July 13, 2017 the formerly named Holbeck Road bridge was renamed the Mary Frances Housley Memorial Bridge “serving as a reminder to generations to come of [Housley’s] selfless act of bravery,” stated the proclamation signed by Knoxville Mayor Madeline Rogero.

A resolution, requested by Knoxville Council Chairman Marshall Stair, wanted to “recognize, honor, and memorialize the personal sacrifice of Mary Frances Housley’s own life.” Council members unanimously approved the proposal in May and contributed $250 for signage for the project.

According to a May 22, 2017 Knoxville Focus article, Housley – known to her friends and family as “Frankie” — grew up in the Fountain City neighborhood in northern Knoxville. Hero Fund records indicate that her father was an advertising salesman and her mother was a registered nurse, living under modest circumstances. Housley attended Central High School, participating in bowling, science, commercial, and glee clubs, as well as the honor society. After graduation, she moved to Jacksonville, Fla., where she became a flight attendant in 1950.

“A very popular girl who was always full of life,” is how relatives described her in a 1951 article published in The Tennessean. Her roommate, Peggy Egerton, was quoted in Reader’s Digest as saying Housley “loved people.”

On Jan. 14, 1951, five months after starting her career in aviation, Housley, 24, was the sole flight attendant on National Airlines Flight 83 from Newark, N.J., to Philadelphia. The plane carried 25 passengers and two pilots, in addition to Housley.

According to the Hero Fund’s report, at the Philadelphia airport, melted snow 1 inch deep covered the ground, a light rain was falling, and air temperature was 33 degrees. The pilot brought the airplane down for landing 3,000 feet from one end of the runway, but noted immediately that he had misjudged his position and that the momentum of the airplane would carry it beyond the runway. The airplane continued at high speed, left the runway, skidded across a ditch and came to rest on a roadway near the airport. The fuselage and fuel tanks, containing 1,550 gallons of gasoline, ruptured. The gasoline caught fire and flames, 10 feet high, enveloped a wing section adjacent to the cabin door. They spread toward the fuselage and into the ditch below the cabin door.

Housley flung open the cabin door and, standing in the doorway, beckoned passengers to come toward her, while the pilots escaped through a cargo hatch. Taking 4-month-old Brenda Joyce Smith of Norfolk, Va., from a seat, she stood near the door and instructed passengers to jump out of the plane to safety. Flames lapped the lower edge of the doorway and broke through the cabin wall. Maintaining her station near the door, Housley continued to direct the passengers from the airplane. She loudly exhorted several women to jump from the doorway despite the flames, but they shrank back into the cabin. Dense flames engulfed the doorway. Firefighters extinguished the flames and found Housley on the cabin floor with Brenda in her lap. They and five other people had perished in the fire.

Despite being trained to abandon the aircraft when in danger of losing her life, Housley allowed 19 people to exit and maintained her position when others hesitated to leave the plane.

“The stewardess could have escaped easily if she had not tried to save the passengers,” said Richard Gordon Benedict, a passenger who jumped from the plane, as reported in a Jan. 15, 1951 New York Times article.

Housley was posthumously awarded the Carnegie Medal nine months after her death. The bronze medal was given to her parents.

“Mary Frances’s story really struck a chord with me spiritually,” Hammond said. “She had her whole life ahead of her, but she did not hesitated to get people out of that burning airplane. It really reflects the beauty of the human spirit.”

grave marker to the headstone marking Housley’s grave. John Housley traveled to Knoxville, Tenn., to

see the dedication of the Mary Frances Housley Memorial Bridge on July 13.

Housley’s nephew, John H. Housley III, traveled from Jacksonville to Knoxville to attend the bridge dedication, and was also able to visit Housley’s grave and affix a Carnegie Hero grave marker to her headstone. Procuring the grave marker had been initiated by Hammond.

“It was an honor to put that hero marker on my family’s grave marker,” John Housley said. “It was really emotional.”

Hammond is also working to raise funds to erect a life-sized statue of Housley in Fountain City Park, a project that garnered the attention of Betty Desjardins, one of the 19 people Housley saved.

Desjardins was 18 months old at the time of the plane crash and was able to exit the plane with her mother and aunt, thanks to Housley’s instructions and cool head. It was Desjardins’s infant sister that Housley was holding when she died.

“I think the story of Mary Frances Housley is amazing,” said Jennifer Seal, the daughter of Desjardins. “I come from a long line of strong, courageous women and Mary Frances Housley ties into our family story quite well. It doesn’t even surprise me at all that she crossed paths with our family.”

Hammond was able to provide Desjardins with her sister’s birth certificate and aid the family in finding the unmarked grave of little Brenda Smith. Desjardins said she and her sister plan to travel to Philadelphia to purchase a headstone for the grave.

“If it hadn’t been for [Housley] our family would have stopped,” Desjardins said. “I can’t believe there would be a woman that young who could be that brave.”

–Jewels Phraner, outreach coordinator

15:13 calls to mind those in the Hero Fund’s 113-year history whose lives were sacrificed in the performance of their heroic acts. The name identifies the chapter and verse of the Gospel of John that appears on every medal: “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” Of the 9,971 medal awardees to date, 2,035, or 20 percent of the total, were recognized posthumously. They are not forgotten.

Related articles:

- ‘Atomic Age’ comic books tell the stories of Carnegie heroes of the ’40s and ’50s

- Roadway marker tells story of Carnegie hero

- December 2017 edition of imPULSE

- New editor Jewels Phraner helms Commission newsletter

Return to imPULSE index.

See PDF of this issue.