Thanksgiving Day, Nov. 17, 1958. The Old Man was at last headed home.

His ordeal had begun a day earlier when a neighbor had worriedly told him, “The young fellow is still out on his boat.”

“Call the Coast Guard,” The Old Man said.

“Just don’t you go out.”

Helmer M. Aakvik, age 62, figured he’d make a quick run out on Lake Superior to the nets. Probably, The Kid’s outboard had stopped running. Gas problems again. He’d have to hurry. The temperature was about 6 degrees and dropping. A storm was coming on from the northwest.

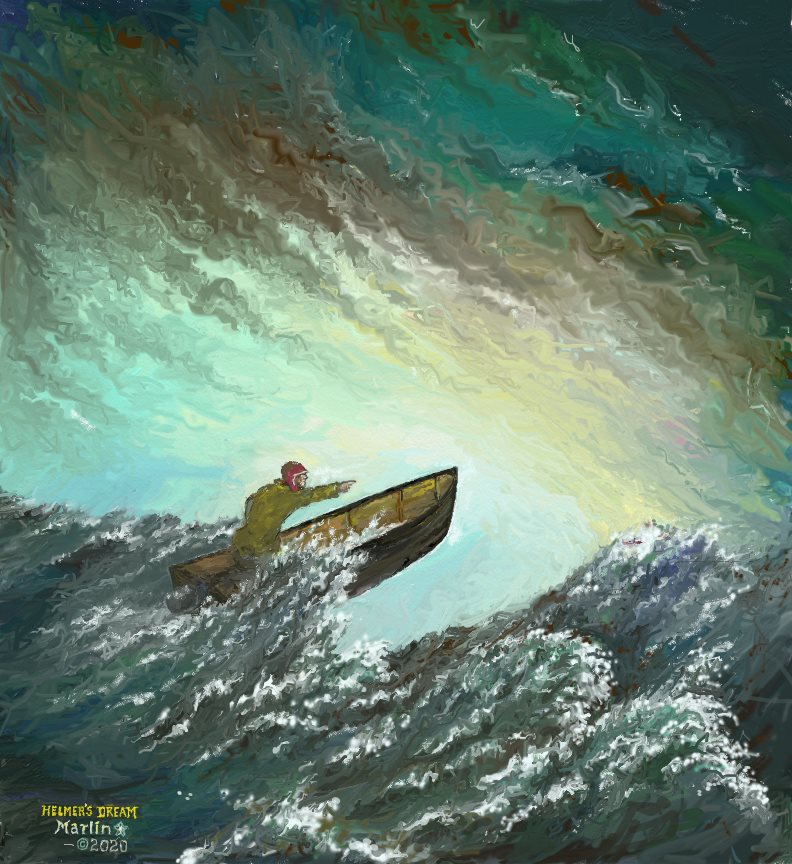

The Kid had not been at the nets, and The Old Man had continued his search. When he was about 8 miles out, he let his engine idle atop a wave for one last look around. There was no sign of Carl Hammer. The waves whistled as they roared past The Old Man’s 17-foot open skiff. He’d never heard them this noisy before. It was time to head back toward shore. His roaring outboard spluttered, then died. The Old Man turned to his outboard, mounted on the transom. It was white with ice.

Again and again, he tried to start it until he was panting from the exertion. The elderly Lockport had been splashed with spray that had frozen. His spare engine, a newer 14-horsepower, two-cylinder Johnson two-cycle, lay in the boat’s bottom. He took the old outboard off and installed the Johnson. He yanked hard on the starter cord, but there was not even an encouraging whuff or slight backfire. His most dependable, newest engine did not start. It had rolled around in the icy bilge water too long. A rogue wave reared over the boat, swamping it. His boat was riding dangerously low in the water.

The old Lockport had been his fishing partner for many years. With a last farewell, he threw it overboard. His skiff was lighter now by more than a hundred pounds. The boat’s freeboard lifted an inch or two.

He had to fix the outboard. Taking off his gloves, baring his skin to the frozen metal, he twisted the engine’s gas line off by hand. No gas was coming out. The Old Man stuck the line in his mouth. The raw rubber, soaked in gasoline, made him gag. He blew — and the ice block popped out. The heat from his mouth had melted it. He reattached the gas line and hauled on the starter cord. With a roar, the engine came to life.

Powering into the onrushing breakers, the skiff’s planks were flexing and the fastenings were pulling loose. The boat was pounding itself apart. He turned off his engine. Without power, his boat cocked broadside to the waves, a dangerous position.

The Old Man hefted a 50-pound fishing crate over the side. The old skiff swung around and the bow cocked to the wave: his boat’s best sea-keeping position. His improvised sea anchor was working.

In his wooden seat, The Old Man could only watch as waves came like dark walls out of the night. They rose high and crashed into the groaning old boat. He could feel its agony as it wracked forward and sideways in the crashing waves. His eyebrows were laced with ice; his eyes were burning orbs from the spray. His unprotected face was painfully cold. His mind was growing slack with fatigue.

Back on shore, he imagined, his small Norwegian community would be preparing Thanksgiving Day feasts. Families had gone all the way to Grand Marais, Minnesota, to pick out hams. Maybe they were roasting right now in hot ovens. And there would be pumpkin pies, a Thanksgiving tradition. He had been out over 16 hours with nothing to eat or drink.

Spray slopped over the bow and froze. If the ice built up too much, his boat would roll over in the waves. He had taken his ax along, and he chopped ice off his wooden boat.

The Kid, he knew, didn’t carry an ax so he had nothing to chop away ice as his boat also would begin to sit lower and lower in the water, getting top heavy.

The Old Man’s mind drifted. Maybe Carl was still afloat; he thought he saw something in the next wave train. There. Near the crest. Another boat? He knew he was fatigued. He tried not to let his mind play tricks on him. Was it just a dream?

Probably, The Kid had slumped down and gone to sleep, worn out from the cold. His boat would cock sideways into the waves and, top heavy with ice, would roll over.

The Old Man was tired. It would be easy to slump in his own seat, bend his head down to his chest, as if in prayer, and let the motion of the boat rock him into slumber. But to sleep was to die.

The moon came out, and The Old Man admired the beauty of the spray by moonlight. It glistened white, surreal and ethereal around him.

Something gleamed white in the water. Ice now surrounded his boat. The Coast Guard boat powered through one fog bank and into another. The temperatures hovered around zero degrees.

“There!” a crew member yelled.

Something white and ice-covered bobbed up eerily above the fog. His face and beard glistened with frost; his hat was coated with inches of ice. He rode in a nearly swamped boat that was itself a block of ice. It was The Old Man.

As they entered Hovland’s (Minnesota) harbor, cheering rolled across the waves. The Old Man was amazed. “There must have been a hundred people,” he would later recall.

He shrugged off help. “I can still walk,” he said. “I’m no cripple.”

He protested when they wanted to rush him to get medical help. “As if I needed a hospital,” The Old Man snorted. “I only froze two toes.”

A reporter from the Duluth News Tribune asked him if he prayed to his God for help during the long night. “No,” he allowed. “There’s some things a man has to do for himself.”

A neighbor rushed to her kitchen and brought out a fried egg sandwich. It was accompanied by a pint of hot coffee. At long last, Helmer ate his Thanksgiving dinner. He was grateful.

After Helmer was brought to shore in the Coast Guard boat, his own boat was lost. Its more than 4 inches of ice caused it to turn over and go under shortly after it was abandoned. It would not be towed.

The Kid’s boat was lost, too, somewhere on Lake Superior. Neither he nor his boat were ever found. He had planned to get to his nets, about a mile and a half out on the big lake, and to get back again before the storm. He never made it. He had dressed in his usual fishing gear, including a cotton work suit. He had not taken extra gasoline, extra clothing, and no ax or sea anchor.

The Old Man figured he’d meet up with The Kid at the nets and bring him home. But hours before, water in The Kid’s gas tank had frozen. Without an engine, he was blown out to sea.

In an era of hard times throughout the country, the reporting of a selfless old man going out in an ice storm to rescue a young villager caught the interest of a nation. North Shore fishermen, often immigrants from Norway, were recognized as incredible boaters who braved great odds for their families and friends. That was the Thanksgiving gift that emerged from Helmer’s quest. He brought honor to his village and to the North Shore. For his courage and survival, he was awarded the Carnegie Medal. He became the real-life “Old Man and the Sea” and was celebrated by Reader’s Digest magazine under the title, “The Legendary Triumph of Helmer Aakvik.”

— Marlin Bree

Marlin Bree of Shoreview, Minnesota, is an ex-Duluthian. This story is excerpted and adapted from Bree’s 2020 book, “Bold Sea Stories.” His website is marlinbree.com.

This article first appeared in the Nov. 24, 2020, edition of the Duluth News Tribune. It was reprinted with permission from the author Marlin Bree.